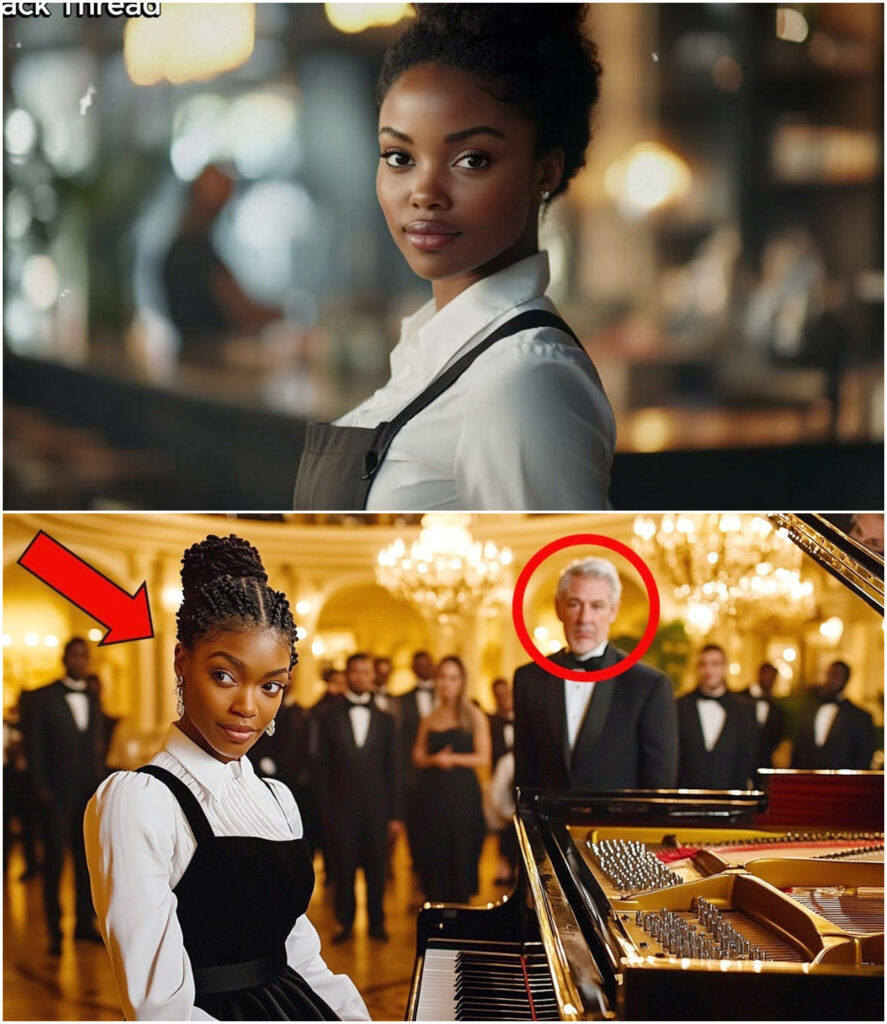

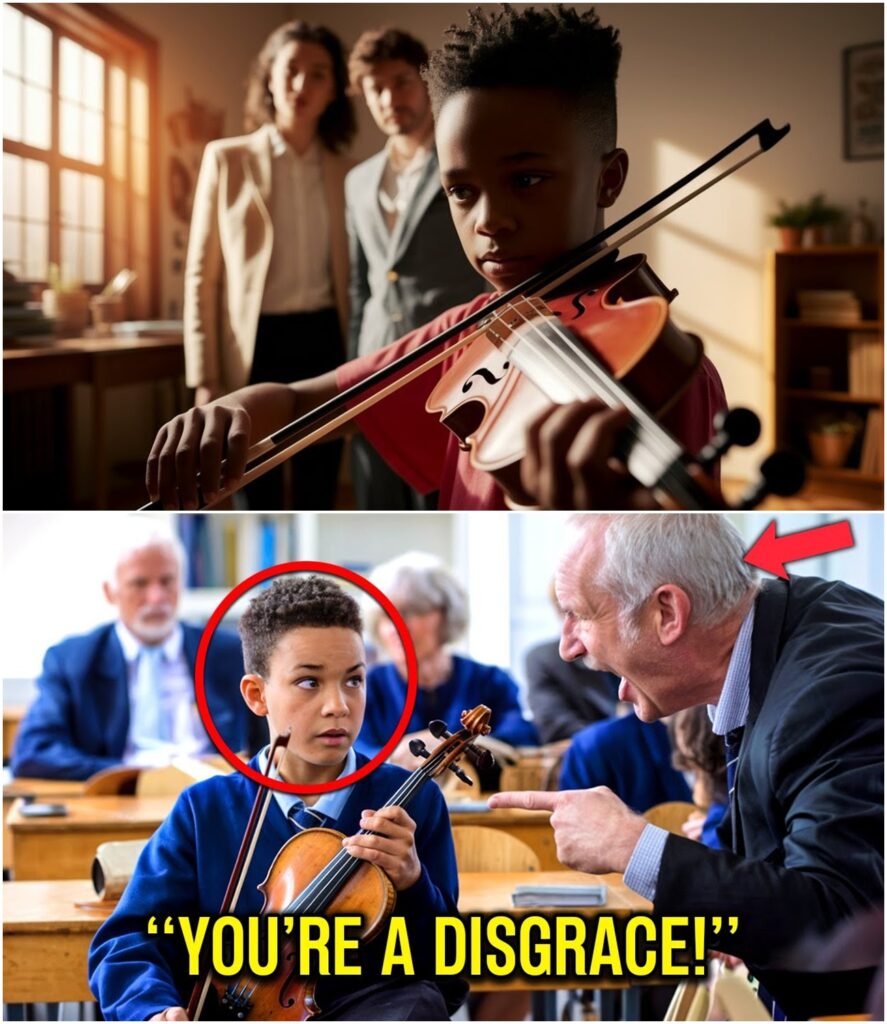

Cop Dumps Food on Black Man for ‘Looking Dirty’ — Froze When He Said “I’m Deep Undercover”

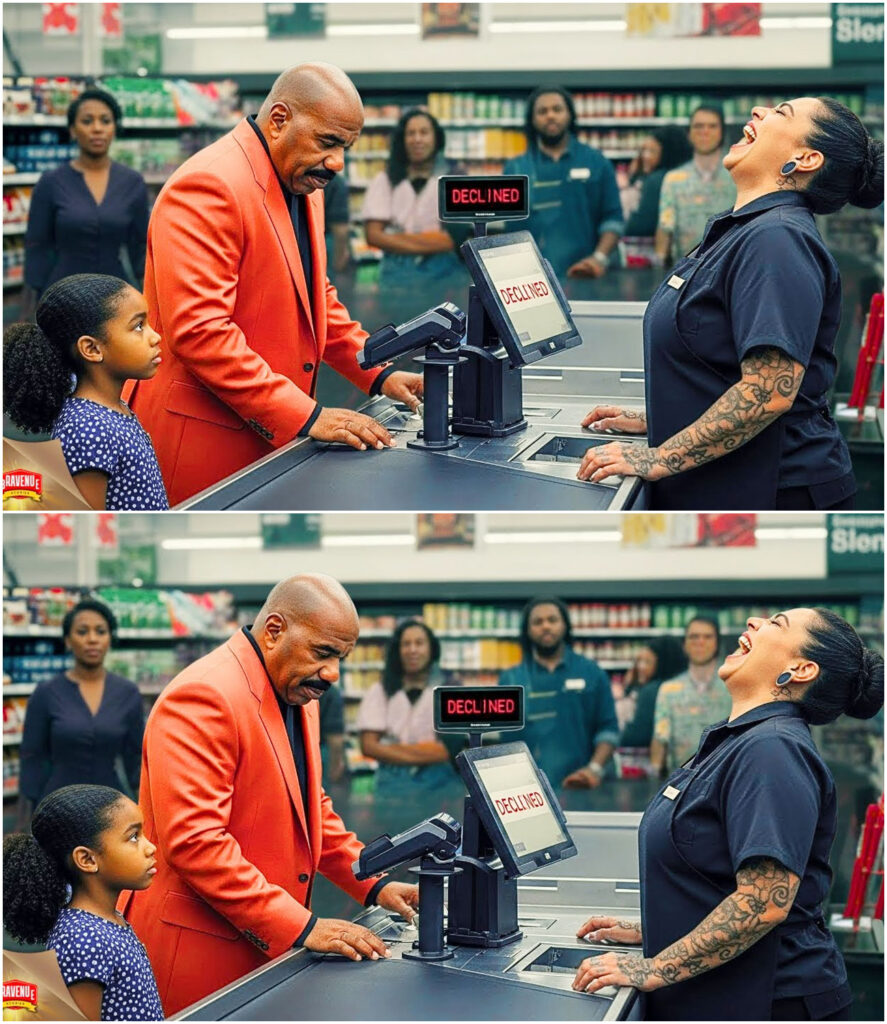

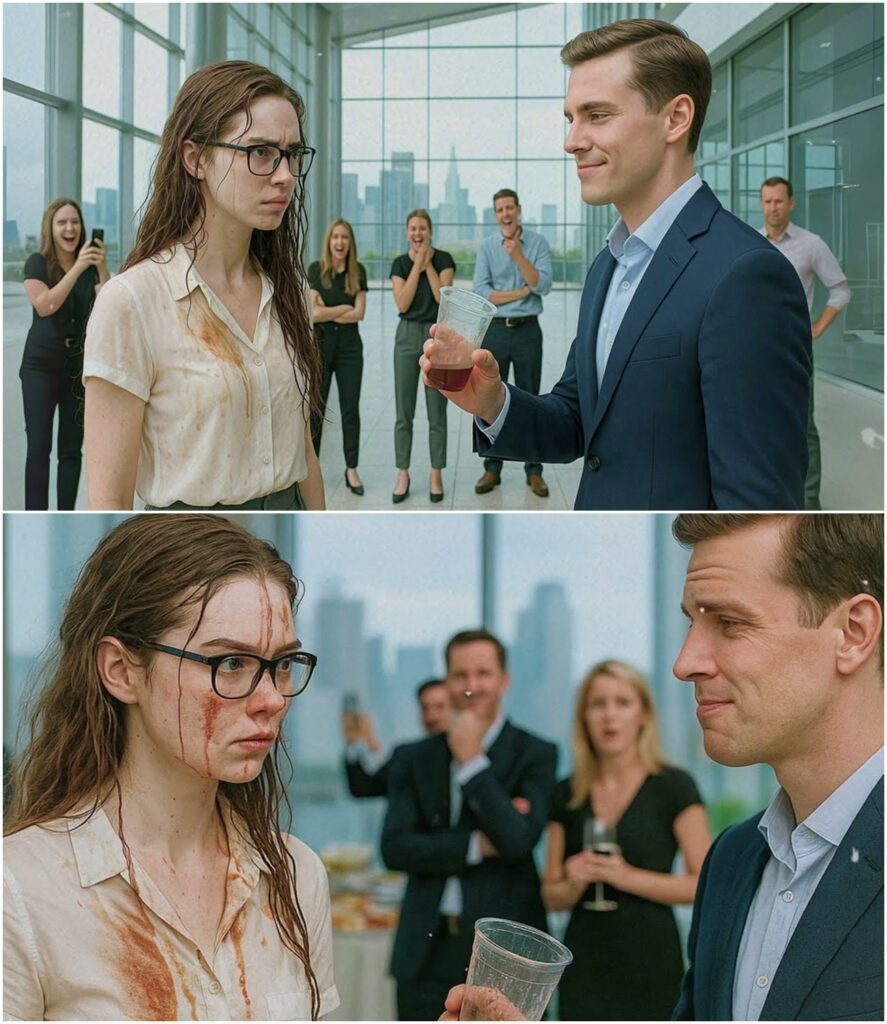

You’re disgusting. It’s 8:45 on a Thursday morning in downtown Riverside. A cop stands over a black man on a bench. The man has a hot dog, a paper cup of coffee. He looks up. Sitting here eating like this. You’re filthy. Look at your clothes. You smell like garbage. A black man sits on a bench. Hot dog in one hand, coffee in the other.

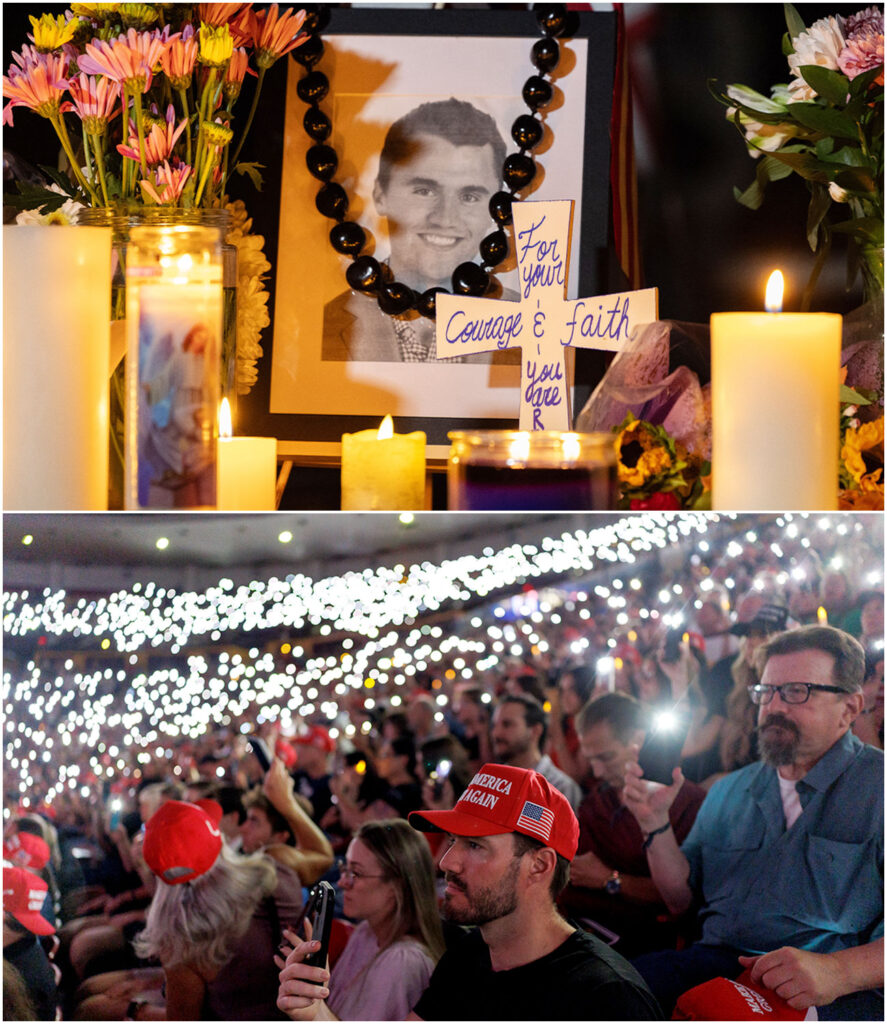

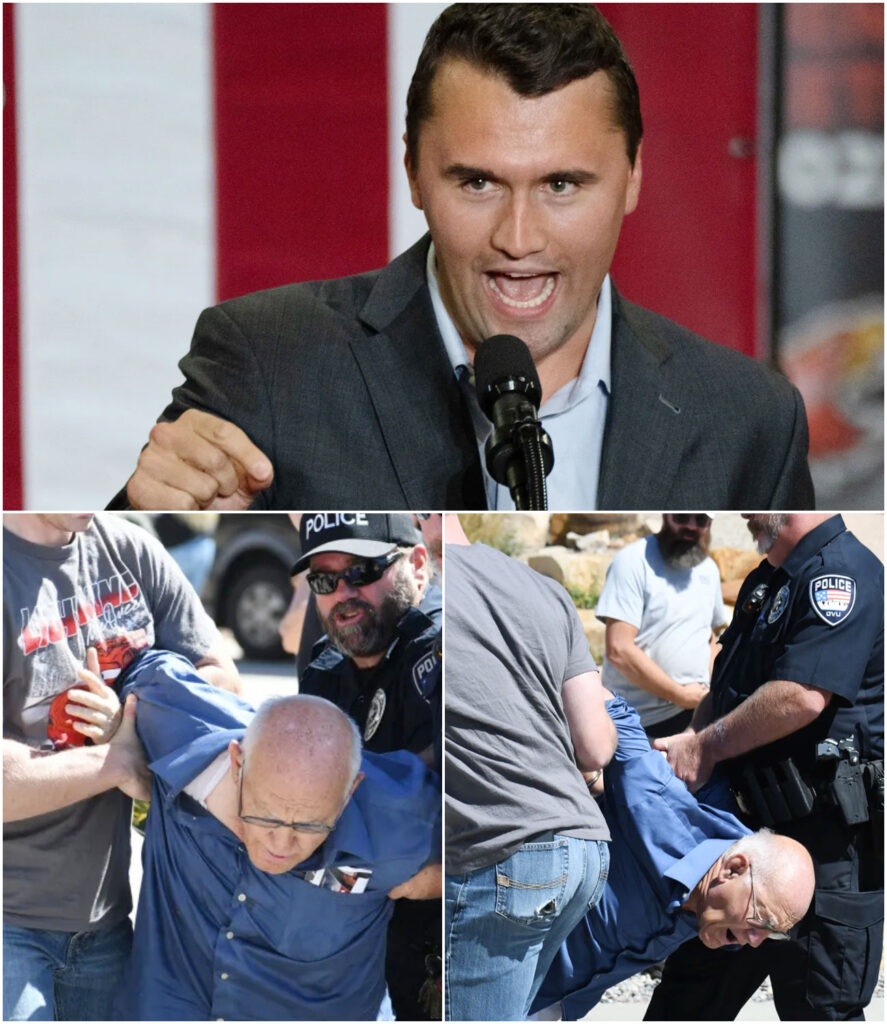

He looks up calm. Just having breakfast, officer. Not here. You’re not. This is a family park. People don’t want to see this. I’m not bothering anyone. You are the bother. The cop steps closer. Stand up. What happens next takes 11 seconds. A hot dog crushed under a boot. Coffee poured onto a man’s head in front of eight witnesses. Four phone recordings.

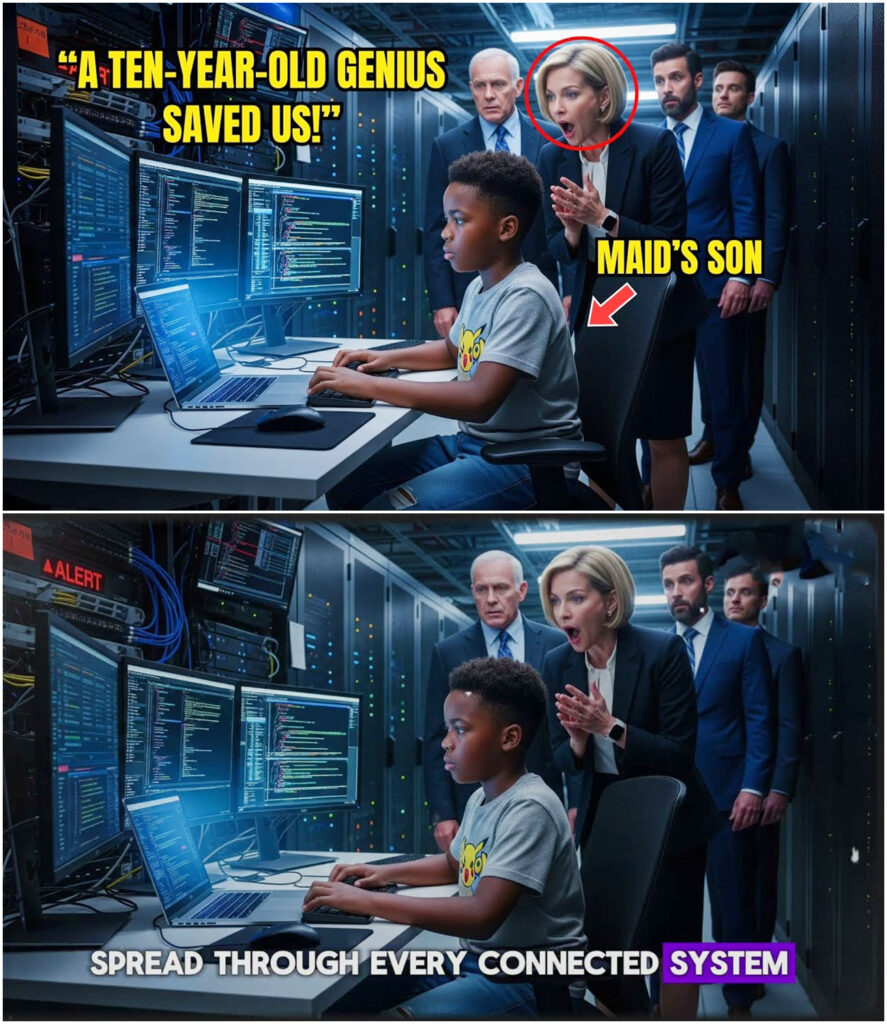

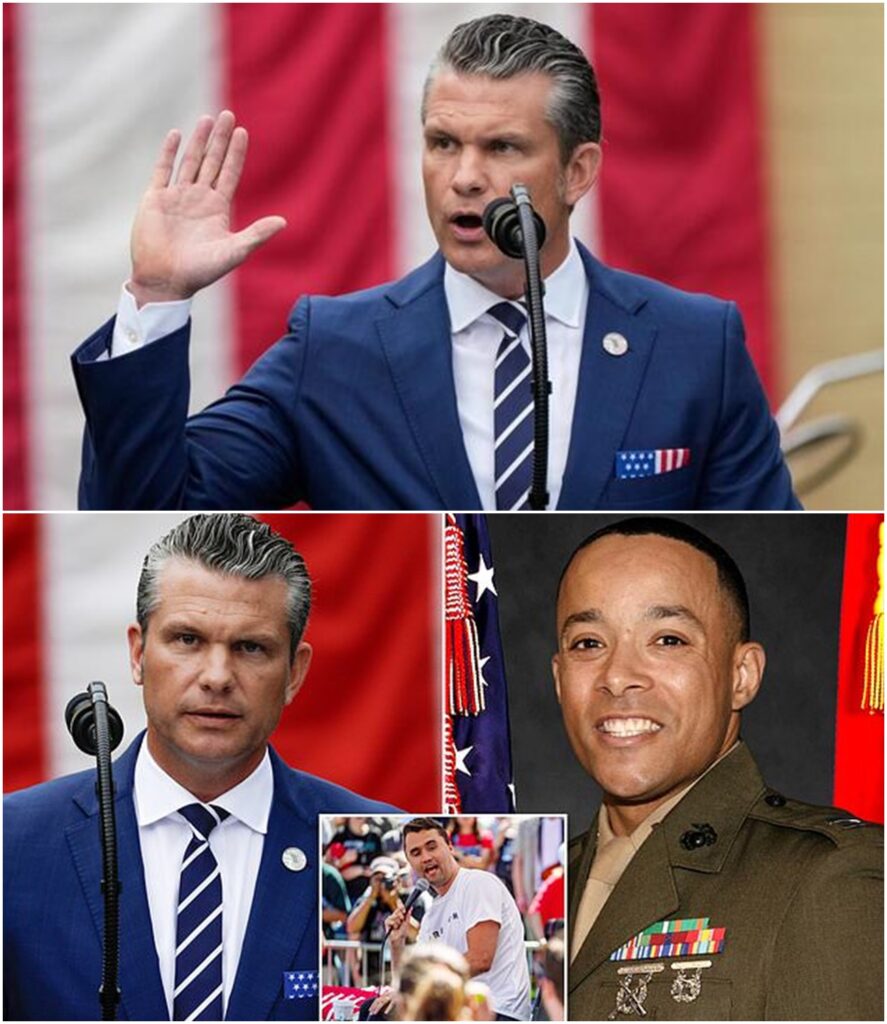

Then the man on the bench says something. Five words that make the officer freeze completely. This is the story of that moment. Rewind 8 weeks. Detective Derek Isaac Bennett sits in Captain Hayes’s office on a Tuesday afternoon in January. Narcotics division. Narcotics. 12 years on the force. 14 commendations. Zero complaints.

Hayes slides a file across the desk. Missing persons reports. 14 girls ages 15 to 17. All last seen in or around downtown Riverside Park. Sex trafficking. Hayes says, “We think it’s disguised as a homeless outreach program. Vans come through, offer food and shelter. Girls get in, never come back.” Bennett opens the file. Faces stare back at him. School photos smiling. Alive.

What do you need? Someone who can get close. Someone they’ll trust. Hayes leans back. You’d have to go deep undercover. No badge visible. No backup nearby. For how long? However long it takes. Bennett thinks about his daughters. Maya, 6 years old. Jordan, nine. He thinks about 14 other fathers who don’t know where their children are sleeping tonight. I’m in. That was 8 weeks ago.

Now, Bennett hasn’t showered in 4 days. His clothes come from a donation bin behind St. Michael’s Church. Jeans with holes in the knees, a jacket with a broken zipper, shoes held together with duct tape. He’s grown his beard out, patchy and unckempt.

He sleeps in his car three nights a week to maintain the illusion. The other nights, he goes home. Maya hugs him and wrinkles her nose. Daddy, you smell different. working on something important, baby. His wife, Angela, doesn’t ask questions anymore. She just sets his dinner plate in the microwave and goes to bed early. Operation Crosswire, 56 Days Deep.

Bennett has established himself as a fixture in the park. The invisible man. Someone who sits on benches and doesn’t make eye contact. Someone the traffickers might eventually approach. Someone desperate enough to do whatever they ask for. $20. He’s gotten close. Two weeks ago, a man in a gray van asked if he wanted to earn some money moving boxes.

Bennett said yes. The man took his phone number, a burner untraceable, and told him to wait. Yesterday, his informant, a former victim who escaped and now works with the police, sent him a message. The tip came through at 7:15 this morning. Big meeting today, 100 p.m. They’re moving girls out of state. Be ready.

So Bennett is here on this bench in Riverside Park, eating a hot dog from the bodega on Fifth Street, drinking coffee that’s already gone cold. He’s positioned himself 40 yard from the northeast entrance where the vans usually appear. His phone is in his jacket pocket. His badge is hidden in a sewn compartment under his shirt. his backup. Two plain clothes officers are parked in an unmarked sedan two blocks away, listening through a wire taped to his chest. Everything is in place. He takes a bite of the hot dog.

Mustard and relish. The taste doesn’t register anymore. After 8 weeks, food is just fuel. The morning is quiet. A jogger passes. A woman walks her dog. An elderly man feeds pigeons near the fountain. Then Bennett hears it. The sound that changes everything. A car door closing. Footsteps on pavement. Heavy. Deliberate. The jingle of keys on a belt. He doesn’t look up. Doesn’t change his posture. Just keeps chewing.

The footsteps stop 3 ft away. A shadow falls across the bench. You can’t be here. Bennett looks up slowly. A police officer, young, late 20s. Badge number 2 tuna 158. Name tag Sullivan. Just eating breakfast, officer. Sullivan’s eyes scan him head to toe. The stare lingers on the torn jeans, the stained jacket, the four days of beard growth. His nose wrinkles slightly. This is a public park, family area.

You’re making people uncomfortable. Bennett keeps his voice neutral. Tired. The voice of someone who’s had this conversation before. I’m sitting on a bench, not bothering anyone. Look at yourself. Sullivan’s voice rises just enough for the jogger passing behind them to hear. You’re filthy. You smell. People come here with their kids.

Bennett sees the woman with the dog glance over. She slows her pace, watching. I’ll move when I’m done eating. No. Sullivan steps closer. You’ll move now. Bennett takes another bite of the hot dog. Slow. Deliberate. He needs to stay in character. A confrontation will blow his cover, but backing down too quickly looks suspicious to anyone watching, including the traffickers who might be observing from a distance. Officer, I have a right.

Rights? Sullivan laughs, sharp, contemptuous. You think you have rights? Looking like that, smelling like that? The elderly man feeding pigeons stops, turns toward them. Sullivan’s hand moves to his belt, not to his gun, to his radio. He keys it. Dispatch, this is unit 12. I’ve got a vagrant situation at Riverside Park, northeast quadrant.

Bennett’s jaw tightens. He hears the word vagrant crackle through the radio speaker. 50 yards away in the unmarked sedan. His backup hears it, too. He needs to deescalate fast. Officer Sullivan. He reads the name tag deliberately. I’m just finishing my breakfast. 2 minutes and I’ll You’ll leave now. Sullivan’s voice cuts through. Stand up.

Bennett doesn’t stand. Can’t. Not yet. The meeting is at 100 p.m. 3 hours away. If he leaves the park, he loses position. 8 weeks of work collapses. Sir, please. I’m not causing trouble. You are the trouble. Sullivan points at the hot dog. Eating out here like an animal. This is disgusting. You’re disgusting. The woman with the dog has stopped walking entirely.

She pulls out her phone. Bennett sees it in his peripheral vision. She’s recording. Good witnesses, but also bad. Witnesses mean attention. Attention means the traffickers might abort. Sullivan notices the phone, too. It doesn’t stop him. If anything, it emboldens him. People like you, he says, voice dripping with disdain. Make this city look like garbage.

We’re trying to clean up around here. Build something decent. And then you show up and ruin it. Bennett feels the wire taped to his chest. His backup is hearing every word. He knows they’re debating whether to intervene, but intervening means revealing his identity, which means losing the operation. He makes a choice. Officer, I understand. I’ll move.

Just let me finish. Sullivan doesn’t let him finish. He reaches down and slaps the hot dog out of Bennett’s hand. It happens fast. The hot dog arcs through the air, lands on the pavement 3 ft away. Mustard smears across concrete. The elderly man gasps audibly. Sullivan isn’t done. He walks over to the hot dog, plants his boot on it, and grinds it into the pavement.

The sound, breadcrushing, meat tearing, cuts through the morning quiet. I said move. Bennett stares at the crushed food, at the bootprint in the mustard. His hands rest on his knees, still controlled. That was my breakfast. You should have thought about that before you decided to stink up a family park.

Bennett reaches for his coffee cup. Still half full, still cold. He raises it to his lips. Sullivan snatches it from his hand. For a moment, Bennett thinks he’s going to throw it away. dump it on the ground like the hot dog, but Sullivan doesn’t throw it. He holds the cup above Bennett’s head, tips it slowly, deliberately. Coffee pours out.

It hits Bennett’s hair first, then runs down his forehead, into his eyes, down his cheeks, soaking into his collar. The woman with the dog says something. Bennett can’t hear it over the rushing in his ears. Eight people are watching now. Four have phones out recording. Sullivan drops the empty cup. It bounces once on the bench, falls to the ground. Maybe that’ll clean you up.

Bennett sits completely still. Coffee drips from his chin. His eyes are closed. His jaw is clenched so tight his teeth hurt. He counts to three, opens his eyes, wipes his face with his sleeve, and makes a decision that will destroy 8 months of work. His voice comes out quiet, calm, colder than the coffee running down his neck.

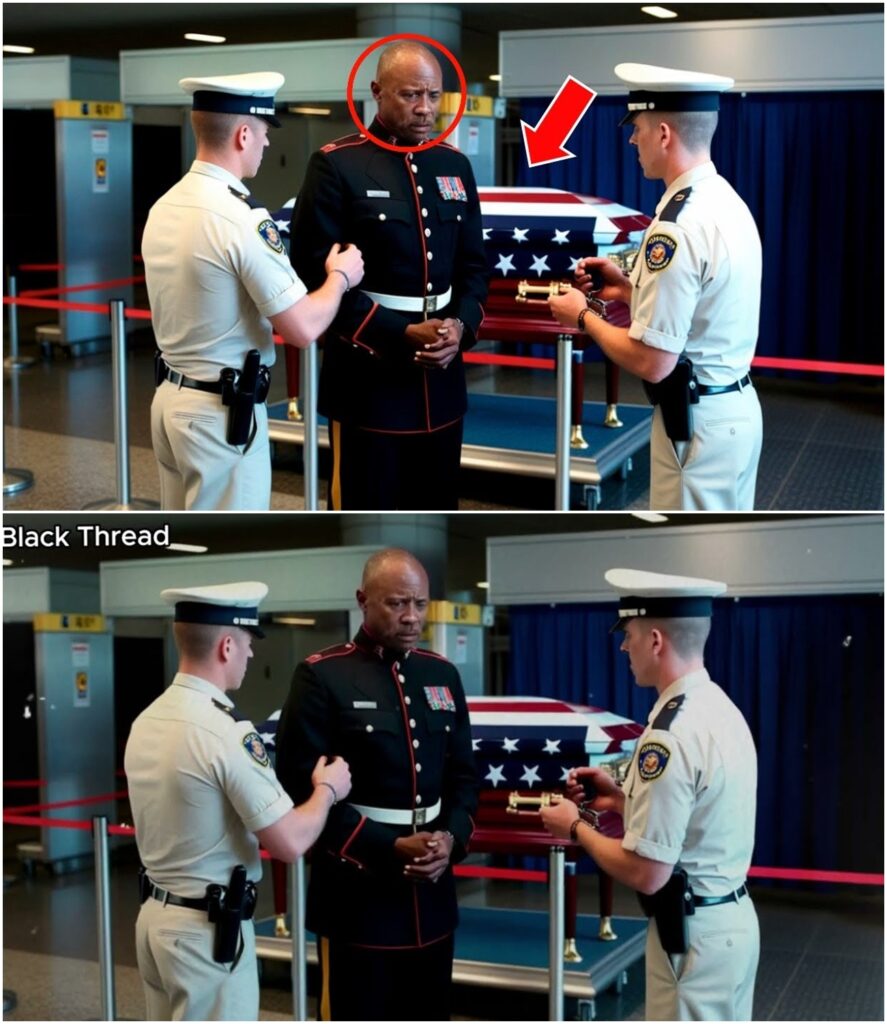

Officer Sullivan, badge number 2158. Sullivan’s smirk falters slightly. The use of his badge number catches him off guard. Bennett reaches slowly into his jacket. 50 yards away, his backup tenses. He pulls out a leather wallet, opens it. Inside, a badge. Gold. Detective grade. I’m Detective Derek Isaac Bennett, narcotics division, deep undercover.

The words hang in the air. Sullivan’s face goes through three expressions in two seconds. Confusion, recognition, horror. His mouth opens. Nothing comes out. Bennett’s voice doesn’t rise, doesn’t shake. You just blew an 8-month operation. You can call Captain Hayes extension 4112 right now. Silence complete. Absolute silence.

The jogger who was passing has stopped midstride. The woman with the dog stands frozen, phone still raised. The elderly man feeding pigeons stares, mouth open. Sullivan doesn’t move. His hand is still extended where it released the coffee cup. His eyes are locked on the badge. 5 seconds pass. 10. Sullivan’s face drains of color, white to gray.

50 feet behind Bennett near the fountain, a man in a gray jacket, one of the trafficking lookouts, stands up from his bench. He sees the badge, turns, walks away quickly. The operation is over. Sullivan finally moves. He steps back once, twice. His hand drops to his side. He doesn’t apologize, doesn’t explain. He turns, walks back to his patrol car.

His steps are too quick, almost stumbling. The car door opens, closes, the engine starts, he drives away. Bennett sits alone on the bench, coffee soaking through his shirt, hot dog crushed on the pavement, badge still in his hand, the wire on his chest, crackles. Detective Bennett, are you okay? He doesn’t answer. Four phones are still recording. The unmarked sedan pulls up 90 seconds later.

Lieutenant Sarah Brennan steps out. Internal affairs. She wasn’t supposed to be here, but she was listening to the wire. She hands Bennett a towel. Are you hurt? Bennett wipes coffee from his face. No, we need to leave now. The meeting at 1 is cancelled. Brennan’s voice is flat. Surveillance just reported. Three men left the park after Sullivan showed your badge. The gray van turned around six blocks out.

Eight months gone. How many got away? All of them. They switched plates, disappeared. Bennett stares at the crushed hot dog on the pavement. His backup, Officer Marcus Shaw, approaches. That idiot just cost us 14 victims. 15? Brennan corrects. They were picking up a new girl today, 16 years old. Run away from Ohio.

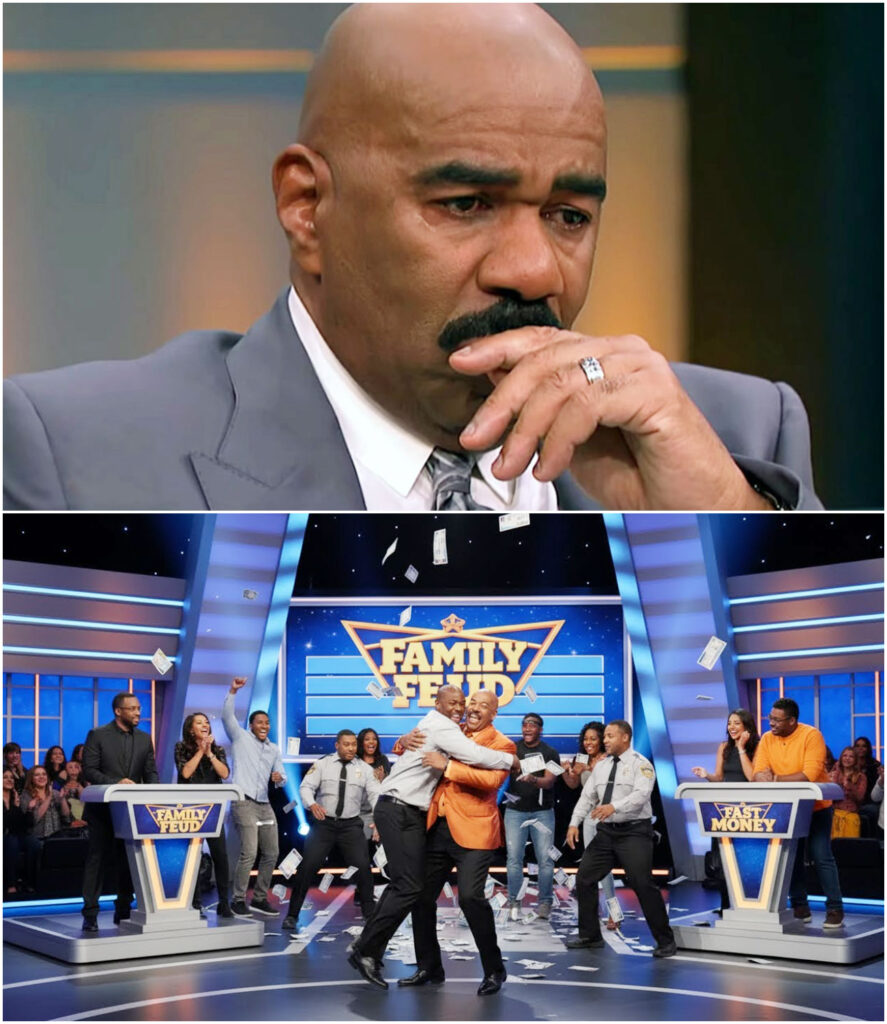

The number hangs in the air. The drive back takes 12 minutes. Nobody speaks. Captain Raymond Hayes waits in his office. The door was closed. Sit. Bennett sits. Still wet. Still smelling like days without a shower. Hayes listens to Bennett’s account without interrupting. When Bennett finishes, Hayes is quiet.

You identified yourself. He poured coffee on my head in front of witnesses. You could have walked away. Keep your cover and let dispatch send more units. The operation dies either way. Hayes exhales. The operation is dead, Derek. Three targets gone. 14 victims moved out of state. This was our only lead in two years. Two years. 43 family interviews.

Hundreds of surveillance hours. 8 weeks in his car. Gone in 11 seconds. What happened to Sullivan? Hayes picks up paperwork. Misconduct report. Destruction of an active investigation. Assault on a fellow officer. Will he be fired? Suspended pending review. Hayes sets the paper down. The union will fight. They’ll say he didn’t know you were undercover.

He poured coffee on someone for sitting on a bench. I know, but proving misconduct is different from proving ignorance. Bennett stands. So, he gets counseling and backpay. Hayes doesn’t answer immediately. We’ll handle this internally. Quietly. Quietly helps no one. Derek. Hayes’s tone sharpens. You’re reassigned.

Effective immediately. Desk duty until this is resolved. The words land like a verdict. Desk duty. Administrative leave. Reports. Background checks. We’ll call it trauma evaluation. I’m not traumatized. I’m pissed. Which is why you need time away. Hayes opens the door. Go home. Shower. See your kids. Come back Monday. Captain, that’s an order.

Outside, Brennan waits. She falls into step beside Bennett. They’re burying this. I know. I’m not letting them. She pulls out a flash drive. Four witnesses, four videos. I collected them before the scene cleared. She hands it to him. Go home. Check your email tonight. 900 p.m. Sarah, go home, Derek.

Bennett sits in his car. Coffee stained, exhausted, flash drive in hand. His phone buzzes. Angela. Maya’s asking when you’ll be home. He types, “On my way.” But first, he sits. Watch the sun climb higher. Somewhere 14 girls are being moved across state lines, and the man who destroyed their rescue is driving a patrol car on paid suspension.

At 2 p.m. the department issues a statement. We are aware of an incident this morning involving two officers in Riverside Park. This appears to be an unfortunate misunderstanding between colleagues. Officer Sullivan has been counseledled on proper identification protocols.

We consider this matter an internal personnel issue and will handle it accordingly. No further comment at this time. The statement uses the word misunderstanding twice. The word assault, zero times. The words sex trafficking operation, not at all. By 900 p.m., the first video has 230,000 views. By midnight, it’s trending on three platforms.

The department’s phone lines are jammed, and Lieutenant Sarah Brennan sits at her kitchen table with a laptop, pulling Sullivan’s personnel file. She opens the first complaint, case number 2022, 0067. Then the second, 2022 0234. Then the third. By 300 a.m. she’s read all 11. Every single one was dismissed as insufficient evidence. Every single victim is a person of color.

Every single incident in downtown Riverside district. She thinks about the word haze used. Misunderstanding. She thinks about 14 girls in the back of a van. She opens a new document and starts typing. The first video comes from Ashley Monroe’s iPhone. 2 minutes 18 seconds. Shaky at first. She’s fumbling to unlock her screen, but then it steadies.

You hear Sullivan’s voice clearly. You’re filthy. You smell. You see the hot dog knocked from Bennett’s hand. You see the boot crushing it into the pavement. You see the coffee poured slow, deliberate onto a man’s head. Ashley posts it at 9:14 a.m. with one line. Cop dumps coffee on black man for looking dirty in Riverside Park.

Man says he’s an undercover detective. By 11:00 a.m. it has 400,000 views. By 100 p.m. it crossed 2 million. The second video is clearer. Shot by Jerome Washington from 30 ft away. Better angle. You can see Sullivan’s face, the contempt in his expression. You can read his name tag, badge number visible. Jerome’s caption, “This is what cleaning up the streets looks like.

” The third video catches the aftermath. Bennett sitting alone, coffee dripping from his chin, the crushed hot dog on the ground, four phones pointed at him like accusations. The fourth video is 47 seconds. Just the audio matters. Sullivan’s voice. People like you ma

ke this city look like garbage. By 6:00 p.m. the hashtag #justice forbennet is trending in 14 states. By 8:00 p.m. it’s national news. The local NBC affiliate runs a 4-minute segment. Detective humiliated during undercover operation. They interview a police accountability expert who uses the phrase racial profiling three times. CNN picks it up at 9:00.

Questions raised about police training after viral video. The department’s statement unfortunate misunderstanding gets quoted everywhere, usually alongside the word inadequate. Comments flood social media. He poured coffee on him like he was trash. Imagine what he does when cameras aren’t rolling. Fire him now. This is why people don’t trust cops. But not everyone agrees. Context matters. We don’t know the full story.

Sullivan was just doing his job. How was he supposed to know? If Bennett looked like a cop, this wouldn’t have happened. The Riverside Police Union issues its own statement at 700 p.m. Officer Sullivan is a dedicated public servant with 3 years of exemplary service. This was an honest mistake made in a challenging situation.

We stand behind him and ask the public to reserve judgment until all facts are known. Officer Sullivan has received threatening messages and asks for privacy during this difficult time. The statement mentions Sullivan’s safety, not Bennett’s humiliation, not the 14 victims. At Bennett’s house, Maya watches her iPad before dinner.

Angela tries to take it away, but Mia’s already seen the video. Daddy, why did that man pour coffee on you? Bennett kneels down, eye level. Because he made a mistake, baby. Was it because you’re black? Angela’s breath catches. Bennett chooses his words carefully. Some people make judgments about others based on how they look. That’s wrong, but it happens.

Did you tell him he was wrong? I did. Did he say sorry? Bennett pauses. No, baby, he didn’t. Maya thinks about this. He should say sorry. You’re right. He should. That night, Bennett checks his email. The message from Brennan arrives at 9:04 p.m. Subject line: You need to see this. One attachment, a PDF, 47 pages.

The first page is a personnel file, Officer Troy Sullivan, badge 2158, hired June 2021. The second page lists complaints, 11 total. Bennett reads through them slowly. Case 202200067. Latino man. Sullivan called him dirty and suspicious. Dismissed. Insufficient evidence. Case 2022 0234. Black woman. Sullivan told her she didn’t belong at a bus stop. Dismissed.

Complainant didn’t cooperate. Case 2023 019 mine. Black man. Sullivan pushed his food cart and told him to move along or get arrested. Dismissed. Conflicting accounts. All 11 complaints. All people of color. All in downtown Riverside district. All dismissed. Every report signed off by the same investigator. Captain Raymond Hayes.

Bennett’s hands shake as he scrolls. At the bottom of the email, Brennan has written one line. This wasn’t a mistake. This is a pattern, and I’m going to prove it. Bennett reads through the complaints again, slower this time. In complaint number seven, the victim, a black teenager, wrote, “The officer said people like me make property values go down. He said businesses complained.

” Businesses. Bennett opens a new browser tab. Types: Downtown Riverside Business Improvement District. The first result is a website. Professional polished photos of new condos and trendy restaurants. Mission statement. Enhancing quality of life and economic vitality in downtown Riverside through strategic partnerships and community engagement. Board of Directors. 12 names. CEOs.

real estate developers, property management firms. At the bottom of the page, a press release from November 2023, BID partners with Riverside PD on clean streets initiative. Bennett clicks the link. The release is three paragraphs long.

Corporate language phrases like public safety and community standards and visible improvements. One sentence stops him cold. Thanks to our partnership with law enforcement, we’ve seen a 42% reduction in quality of life complaints and a 12% increase in property valuations quarter over quarter. Quality of life complaints. Bennett thinks about Sullivan’s words. We’re trying to clean up around here. He thinks about the 11 dismissed complaints.

He thinks about the phrase Hayes used handled internally. His phone rings. Brennan, you saw the email. I saw it. There’s more. Her voice is tight. I pulled Sullivan’s overtime records. I need you to see the numbers. Brennan sends the financial records at 11 p.m. Bennett opens the spreadsheet. Column after column of numbers, officer names, hours, overtime, pay.

He scrolls to Sullivan’s row. Fourth quarter 2023 before clean streets initiative. Overtime $8,100. First quarter 2024 during clean streets. Overtime $28,400 350% increase. Bennett cross references dates. Initiative launched January 2nd. Sullivan’s first spike January 7th. Six other officers show similar patterns. All downtown Riverside patrol, all with increases between two and 400%.

Combined overtime increase $180,000 in three months. He calls Brennan. Where’s this money coming from? The B. Her voice is exhausted. Business improvement district. I pulled their financials, their public record. Line item from January. Law Enforcement Partnership Enhancement 150,000 annually. They’re paying the department.

It’s structured as a grant. Legal, but look at the timing. Be it approves funds in December. Initiative launches in January. Overtime spikes immediately. Bennett stares at numbers. Officers get paid more to patrol. B gets fewer homeless people. Fewer undesirabs. Brennan’s voice hardens. That’s their word from meeting minutes.

Quote, “Partnership with RPD has resulted in significant reduction of undesirabs in high value corridors. Send everything.” The files arrive. 43 documents. BI meeting minutes. November 2023. Director Victoria Ellis presenting property values up 38% year-over-year. However, stakeholder concerns about street level aesthetics, particularly vagrant populations, recommend enhanced law enforcement partnership before Q2 investor meeting.

December minutes framework established with Chief Hayes for increased patrols. Officers are incentivized for quality of life enforcement. January minutes 47 contacts logged. Significant reduction in panhandling, loitering, property inquiries up 12%. 47 contacts. Bennett opens another file. Community outreach log. Internal document. 47 entries January through March.

January 7th. Male black age approx 35. Sleeping on a bench. Advised to relocate. January 9th. Female Latina, age approx 28, panhandling, cited for solicitation. January 14th, male, black, age approx 42, selling newspapers without permit, confiscated. Every entry has an identical pattern.

Race identified, age estimated, relocated or cited, 47 people, 42 are people of color, 89%. Bennett opens Sullivan’s file again, different angle. All 11 complaintants appear on the outreach log. Jerome Washington, complaint 2023 0119, is entry 23. Male, black, age approx 40, food cart blocking access, became argumentative. Washington’s complaint described it differently.

Officer Sullivan pushed my card and said I was lowering property values. Hayes dismissed it. Conflicting accounts. Kesha Daniels. Complaint 2022 0234. Sullivan told her she didn’t belong at a bus stop. Log entry. Nine. Female, black, age approx 30, loitering at a transit stop. No valid destination. Dismissed. Complainant didn’t cooperate. Every complaint has a corresponding log entry. Every entry submitted by the same seven officers whose overtime tripled.

Body camera records. Next. Sullivan’s camera. 23 malfunctions in 12 months. All 2 to 8 minutes. All immediately before outreach log entries. January 7th, malfunction 6:23 to 6:31 a.m. Log entry 6:28 a.m. March 14th malfunction 8:44 8:52 a.m. Bennett incident 8:47 a.m. Perfect pattern.

The cameras, Bennett says when he calls back, tech unit confirmed. These don’t fail spontaneously. Manual deactivation only. He knew every time. There’s more. Sullivan had three training mentors. Thomas Okconor, William Douglas, George Turner. Bennett recognizes the names. Veterans 20 plus years each. What about them? Same complaints, older ones.

Okconor has 14 going back to 2009. Douglas has nine. Turner has six. Same pattern, same dismissals. 11 + 14 + 9 + 6 40 total complaints. Hayes signed everyone. Brennan says 15 years of burying these. The scope hits Bennett physically. Not one officer, not four. Institutional. What do we do? Full report, documentation, timeline, financial records. I’m submitting to the inspector general tomorrow. Bypassing Hayes entirely.

That’s career suicide. 14 girls are missing. Derek Sullivan destroyed your operation because he was trained to see people like you as problems by men doing this 15 years with real estate money. She’s right. What do you need? Your statement detailed everything. When? Tonight. filing at 8:00 a.m. 11:47 p.m. I’ll write it now. At 1:30, Angela finds him still typing.

You need sleep. I need to finish. She reads over his shoulder the complaints, financial records, camera logs. Oh my god, worse than we thought. She sits. What happens when you submit? The IG opens an investigation. Could take months, years. And Sullivan probably fired eventually. Hayes, the mentors. Depends what they find. The girls. Bennett stops typing.

I don’t know. Angela takes his hand. Not your fault. I should have walked away and let those 11 complaints stay buried. Those 47 people think nobody cares. You showed them someone does. He finishes at 3:18 a.m. Nine pages. Every detail. Subject line, my account. Brennan replies instantly. Thank you.

Tomorrow will be loud. Bennett doesn’t sleep. He sits in darkness thinking about Jerome Washington, Kesha Daniels, 45 others whose names he doesn’t know. told they don’t belong. Logged as contacts turned into funding and promotions and overtime. Sullivan’s boot crushing the hot dog. B minutes. Significant reduction of undesirabs. Maya asked. Did he say sorry? At 7 a.m.

his phone buzzes. Unknown number. Stop digging. Your family is beautiful. It would be a shame if something happened. attached a photo. Maya at her school playground yesterday, taken from outside the fence. Bennett’s blood goes cold. Bennett forwards the photo to Brennan immediately, then to his captain. Then he calls Angela.

Keep Maya home from school today. What? Derek, what’s wrong? Someone took a photo of her at the playground yesterday. silence. Then Angela’s voice sharp with fear. Who? I don’t know, but they just sent it to me with a threat. I’m getting the kids. We’re going to my sisters. Good.

Don’t tell anyone where, not even me. I’ll call you from a different phone. Bennett hangs up, dials Hayes. Captain, I need protection for my family. Hayes’s voice is groggy. 7:15 a.m. What happened? Bennett explains. The photo, the text, the threat. Send it to me. Bennett forwards it. Hayes is quiet for a long moment. I’ll have a unit do extra patrols near your house, but Derek, we can’t provide 24-hour protection based on an anonymous text.

Someone photographed my six-year-old daughter. I understand, but we don’t have the resources. Then find them. Bennett hangs up. His phone rings 30 seconds later. Unknown number again. He answers. Says nothing. A woman’s voice, professional, cold. Detective Bennett, my name is Victoria Ellis.

I’m the legal counsel for the Riverside Police Union and director of the Downtown Business Improvement District. The B director. Calling his personal phone. How did you get this number? That’s not important. What’s important is that we have a mutual interest in resolving this situation quietly. Someone just threatened my daughter. I’m calling to ensure that it doesn’t escalate.

Her voice remains perfectly calm. The union is very concerned about Officer Sullivan’s well-being. He’s received over 300 threatening messages in the past 18 hours. Death threats. His home address was posted online. He poured coffee on my head. He made a mistake, a regrettable one. But public crucifixion serves no one.

The union is prepared to offer a settlement, full apology, restitution for emotional distress, and will ensure Sullivan receives additional training before returning to duty. He’s returning to duty. Eventually, after appropriate counseling, Ellis pauses. Detective, you’ve had a distinguished career. 12 years, 14 commendations. You have a family to think about.

Making this situation more adversarial benefits no one, especially not those 14 trafficking victims you’re so concerned about. The mention of the victims makes Bennett’s jaw clench. Are you threatening me? I’m offering you a path forward. one that protects your career, your family’s privacy, and allows the department to handle this matter internally without further media circus. Internal handling is how we got here. 11 complaints buried.

Ellis’s voice cools further. I don’t know what you think you’ve uncovered, but I’d be very careful about making accusations without complete information. The BD’s partnership with the police department is entirely legal and has resulted in significant improvements to public safety and quality of life for law-abiding residents by removing undesirabs.

A beat of silence. I see you’ve been reading meeting minutes out of context. That term refers to problematic behaviors, not people. And I’d advise you to think very carefully before suggesting otherwise publicly. Is that a threat? It’s legal advice. Defamation is a serious matter, as is interfering with a lawful business operation.

The B represents 12 major property holders with substantial legal resources. Bennett’s other line buzzes. Brennan, I have to go. Think about what I said, detective. For your family’s sake, the union will be in touch about the settlement offer. She hangs up. Bennett switches to Brennan. Where are you? She asks immediately. Home. Why? Get to the station now.

Hayes called me in for a meeting. 8:00 a.m. What about the IG report? That’s what the meeting’s about. Bennett arrives at 7:55. Brennan is already in Hayes’s office. So is someone Bennett doesn’t recognize. A woman in a gray suit, sharp eyes. Detective Bennett. Hayes says, “This is Deputy Chief Patricia Morrison, Internal Affairs Oversight.

” Morrison doesn’t offer her hand. Sit. Bennett sits. Morrison opens a folder. Lieutenant Brennan submitted a preliminary report to the Inspector General this morning before it was reviewed or approved through proper channels. That’s a serious breach of protocol. Brennan’s voice is steady. I followed the procedure for reporting suspected corruption that involves my direct chain of command.

You accused Captain Hayes of deliberately burying complaints. I documented 15 years of dismissed complaints with identical patterns, all signed off by the same investigator. Morrison’s eyes are ice. You documented coincidences and drew inflammatory conclusions. You’ve jeopardized ongoing personnel matters and violated multiple officers privacy rights by sharing sealed complaint files.

Those complaints show a pattern. Those complaints were investigated and found to lack merit by experienced investigators following department protocol. Bennett speaks up. 47 people logged in as contacts in 3 months. 89% people of color. That’s not a coincidence. Morrison turns to him. Detective, you’re on administrative leave.

You’re not part of this conversation. I’m the victim of the assault that started it. You’re a detective who broke cover during an active operation, costing the department 8 months of work and significant resources. Your judgment is questionable at best. The words land like punches. Hayes finally speaks. Sarah, you’re reassigned effective immediately. Property crimes. No investigative authority.

Brennan’s face goes white. Captain, that’s the deal you’re getting instead of suspension. Take it. Morrison stands. This meeting is over. Detective Bennett, go home. Lieutenant Brennan, report to your new supervisor Monday morning. And both of you, her voice drops to steal. Stop talking to the press. Stop posting on social media. Stop freelance investigating.

If I hear either of your names connected to this case again, you’re both terminated. Clear? Neither responds. I said clear. Clear. Brennan says quietly. Clear. Bennett echoes. Morrison leaves. Hayes won’t meet their eyes. In the parking lot, Brennan’s hands shake as she unlocks her car. They’re burying it, she says. All of it. Bennett thinks about the photo of Maya, about Victoria Ellis’s voice, about Morrison’s threat. Not if we don’t let them.

Brennan looks at him. We just got ordered to stand down. Since when do you follow bad orders? She almost smiles. Almost. I have a contact. Jamal Brooks, investigative journalist, Riverside Gazette. If we can’t fight this from inside, we fight from outside. Bennett’s phone buzzes. Another text. Unknown number. Good decision at the meeting. Keep making smart choices.

Someone was listening. Or Hayes told them or Morrison did. Bennett deletes the text. Call your journalist. He says 3:00 a.m. Bennett sits alone in his kitchen. The house is empty. Angela took the kids to her sister’s place 4 hours outside the city. She didn’t say where exactly, just called from a gas station.

We’re safe, Maya cried when they left. Why can’t daddy come? Daddy has work to finish, baby. And now Bennett sits in silence. Phone off, laptop closed. He told Brennan not to contact him for 48 hours, but he can’t sleep. 14 girls missing. Moved across state lines while he sat on a bench eating a hot dog.

8 months gone in 11 seconds. 47 people logged like inventory, relocated, advised to move. Their humanity is reduced to spreadsheet entries that justify budget increases. Sullivan drives a patrol car, collects a paycheck, probably sleeps fine. Hayes signs dismissals and goes home to dinner. Ellis uses words like undesirabs in board meetings.

And Bennett sits in an empty house wondering if he made the right choice, if he’d walked away, kept his cover, let the coffee drip, and said nothing. Maybe the operation would have continued. Maybe they’d have arrested the traffickers at 100 p.m. Maybe 14 girls would be safe now, but 47 others would still be invisible.

11 complaints buried. Sullivan was still crushing hot dogs, pouring coffee, and no one would know. Is that a fair trade? 14 victims for 47 others? Bennett doesn’t know. Maya’s question haunts him. Daddy, why did that man pour coffee on you? The easy answer, he made a mistake, baby. The real answer is harder. The man poured coffee because someone trained him to see certain people as problems.

Because someone paid him extra to remove those problems. Because 11 others tried to speak up and got silenced. Because a system turns human beings into contacts and budget justifications. Because Derek Bennett, decorated detective, father of two, 12 years of service, looked like someone who didn’t belong.

The worst part, if he’d been wearing his uniform, Sullivan never would have approached, never would have touched him. The badge protects some people. Only when it’s visible. Bennett thinks about the coffee hitting his head. The humiliation. Eight people watching. Four phone recordings. Sullivan’s face seeing the badge. Color draining. Frozen. Haze. Making noise helps no one. Morrison, stop investigating or you’re terminated.

Ellis, for your family’s sake. Maya’s other question. The one that cuts deepest. Did he say sorry? No, baby, he didn’t. Bennett opens his laptop, powers it on, types an email to Jamal Brooks, Riverside Gazette. Subject: Story you need to hear. body. My name is Detective Derek Bennett. You’ve seen the video.

I’m ready to tell you everything, but I need a promise. If something happens to me, you publish it all. He attaches Brennan’s files, all 43 documents, financial records, meeting minutes, complaint files, body camera logs, the community outreach spreadsheet, everything. His finger hovers over send.

If he does this, there’s no taking it back. Morrison fires him. Union sues. Ellis comes after him with 12 property developers lawyers. Career over. But maybe those 14 girls get found. Maybe complaint 48 doesn’t get dismissed. Maybe the next person on a bench doesn’t get coffee poured on their head. Maybe. Maya asking, “Are you going to give up?” He clicks send. Email whooshes away.

He closes the laptop. Sits in darkness. Phone still off, sitting on the table like an accusation. He doesn’t turn it on. Outside, sun rises over Riverside, the same park where this started, where Sullivan crushed a hot dog and thought he was doing his job. Where Bennett made a choice that cost him everything and might possibly change something.

6 a.m. Bennett falls asleep on the couch. 9:00 a.m. Riverside Gazette publishes a 5,000word investigation. Headline cleaned out. How real estate money bought police protection to gentrify neighborhoods. By noon, it’s national news. Jamal Brooks article doesn’t ask questions. It presents evidence.

43 documents, timelines, financial records, names, numbers, screenshots of meeting minutes with the word undesirabs highlighted. A video compilation embedded at the top. 23 incidents in 18 months. Sullivan, Okconor, Douglas, Turner. Same language, same tactics, same victims. You don’t belong here. Move along.

You’re making people uncomfortable. Different faces, same script. Brooks interviews seven of the 11 complainants. Real names, real faces. They tell their stories on camera. Jerome Washington, 41, food cart vendor. Officer Sullivan pushed my card into traffic and told me I was lowering property values just by existing.

When I tried to file a complaint, they said there wasn’t enough evidence, but I had witnesses. Three people saw it. Nobody asked them. Kesha Daniels, 32, waiting for a bus. He said I looked like I was loitering. I had a bus pass. I showed it to him. He said I didn’t look like I belonged in this neighborhood. What does that mean? I’m black. The neighborhood is gentrifying. You do the math. Seven people.

Seven identical stories, seven dismissed complaints. By 10:00 a.m., the article has 50,000 shares. By noon, national outlets are calling. CNN, MSNBC, Fox News. Everyone wants interviews. By 200 p.m., a protest forms outside Riverside Police Headquarters. Starts with 40 people, grows to 200, then 500. They’re not shouting, not breaking anything, just standing, holding signs. 11 complaints, zero accountability.

Real estate money can’t buy silence. We all deserve dignity. One sign shows Sullivan’s overtime records, $8,100 versus $28,400. The numbers speak for themselves. Bennett watches from his couch. Live news coverage. His phone is back on. 37 missed calls. He ignores them all except one. Angela, are you seeing this? Yeah.

Derek, they’re listening. People are listening. On screen, Jerome Washington speaks to reporters. I thought I was alone. I thought nobody cared. Now I know we were all silenced the same way. But we’re not silent anymore. At 400 p.m., City Council member Patricia Hughes makes a statement.

I’ve reviewed the Riverside Gazette’s investigation. The allegations are deeply troubling. I’m calling for an emergency council session on March 28th. All parties will testify under oath. The public deserves answers. The union issues a response 30 minutes later. Victoria Ellis on camera. Professional controlled.

Officer Sullivan is a dedicated public servant who made an honest mistake in a challenging situation. The union stands behind him. These allegations of systemic bias are unfounded and politically motivated. We will vigorously defend our officers against this character assassination. She doesn’t mention the 47 names on the community outreach log. Doesn’t mention the body camera gaps.

Doesn’t mention the word undesirabs in the B minutes she personally wrote. Bennett’s phone rings. Brennan, you saw the council announcement? Yeah. They’re going to call you to testify. Good. Derek Morrison threatened to fire us. She can’t fire someone for testifying to the city council. That’s retaliation. Even the union can’t protect that.

Brennan is quiet for a moment. What if they ask about the files? How did I obtain them? Tell the truth. You followed protocol for reporting suspected corruption. Morrison says I violated privacy rights. Morrison is trying to scare you. Those complaint files should have been investigated 15 years ago. You did what Hayes should have done. Another silence.

Then thank you for what? For not walking away from that bench. Bennett thinks about Maya. About 14 girls are still missing. About Jerome Washington’s food cart. I couldn’t. That night, Bennett’s doorbell rings. He checks the window first. Habit now. A woman mid-30s. He doesn’t recognize her. He opens the door. Chain still on. Detective Bennett. Her voice shakes.

My name is Carol Mitchell. My daughter disappeared from Riverside Park 6 months ago. She was 16. I saw your interview. The operation you were working on. Was it for girls like my daughter? Bennett’s throat tightens. Yes. Did you find her? The question hangs between them. Not yet, but we’re not stopping. Carol Mitchell nods, wipes her eyes.

Thank you for trying. That’s more than anyone else has done. She leaves an envelope. Inside a photo of a smiling girl, dark hair, braces, school uniform. On the back, written in pen. Melissa Mitchell, age 16, last seen January 19th, 2024. Bennett adds it to the file. 15 victims

now. Brennan calls at 11 p.m. 4 days before the hearing. I found something. What? A manual in Haye’s old office. Locked drawer. Bennett sits up. What kind of manual? Training title. Effective community policing in high transition areas. Subtitle. Internal use only. Written by Raymond Hayes 2014. Read it. Papers. Russell. Brennan’s voice. Objective.

Maintain community standards in areas undergoing economic transition. Target behaviors include loitering, panhandling, public consumption, unauthorized vending. That’s not illegal. Listen. Language guidelines. Avoid explicit references to appearance or demographics. Use terms like safety concern, community complaint, quality of life. Documentation. Minimize paperwork. Verbal warnings preferred.

Contacts should appear voluntary. Bennett’s blood runs cold. They trained them to hide it. More body camera protocol. Officers should be aware equipment malfunctions occur. Use discretion regarding when recording is operationally necessary. That’s instructing them to turn cameras off without saying it explicitly.

Brennan flips pages. Section on homeless populations. Individuals experiencing homelessness often congregate in areas targeted for economic development. Officers should prioritize these areas for quality of life enforcement. Consistent presence and firm but respectful contact discourages problematic behaviors.

Respectful, Bennett repeats, bitter signature page. Hayes wrote it. Three others signed off. Okconor, Douglas, Turner, the mentors. So Sullivan was following training. Exactly. And there’s a distribution list. 23 officers received copies between 2014 and 2023. 23 officers, all taught to see undesirabs as problems. All taught neutral language that means removal.

All taught to minimize documentation. Does Morrison know? No, I found it yesterday. Submit it to the city council public hearing. They subpoena it. They’ll say I stole it. You were investigating complaints. You found evidence. That’s detective work. Brennan is quiet. Then if I do this, Morrison fires me. Probably.

Hayes denies writing it. His signature is on it. He’ll say it’s out of context. Let him explain to Jerome Washington to 47 people on that spreadsheet. Silence. Okay, I’ll do it. But I’m copying everything first, sending one to Brooks. If they bury it, he publishes. Smart, Derek. When Sullivan testifies this manual is his defense. He followed training, followed orders. I know.

won’t make him innocent, but makes Hayes guilty. Bennett thinks about Sullivan freezing, color draining. 5 seconds of silence. Hayes built this system for 10 years, training officers to discriminate efficiently with professional language, tactics that avoid lawsuits while making money. Brennan adds the final piece. B pays the department.

The department pays overtime. Officers do the work. Hayes supervises. Everyone benefits except the 47 people removed. Except them. Bennett looks at the photo on his table. Melissa Mitchell, 16, missing. When’s the hearing? March 28th, 2 p.m. I’ll be there. Union lawyers will tear you apart. Let them try. Brennan laughs short, humorless.

You know the worst part? What if Sullivan had just let you finish your hot dog? None of this comes out. Hayes retires with pension. B keeps paying. 47 becomes 470. Nobody knows. Bennett thinks about the boot crushing mustard. Coffee poured with contempt. Sometimes the worst mistakes expose the biggest truths.

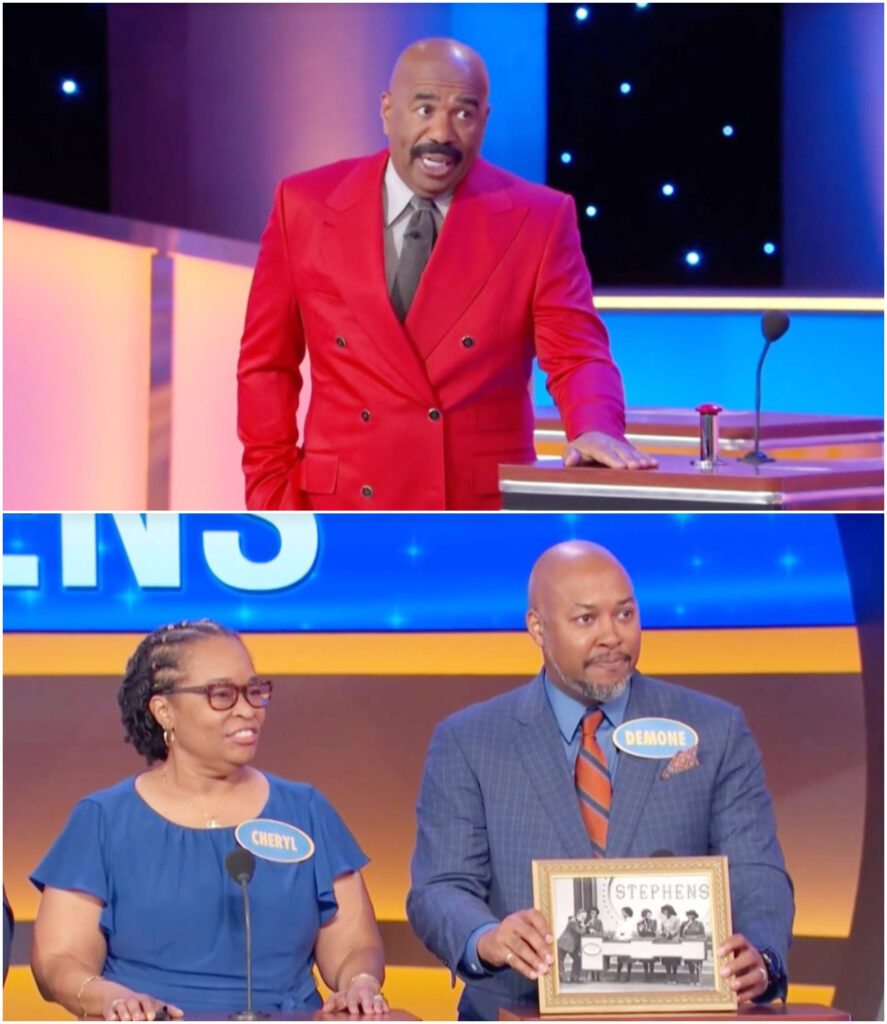

Is that a saying? It is. Now they hang up. Bennett opens his laptop, starts writing testimony. Every detail, every moment, every word Sullivan said. The city council will hear all of it. Outside Riverside sleeps. The park is empty. Benches vacant for now. March 28th, 200 p.m. City Council chambers. 200 people packed into space for 150.

12 cameras overflow watching monitors in the hall. Councilwoman Patricia Hughes gavvels the room to silence. This special session examines allegations of systemic bias in police enforcement and the department’s relationship with the business improvement district. Everyone testifies under oath. Jamal Brooks presents first. 47 names scroll on screen. 89% people of color.

Financial records Sullivan’s overtime 28,43 months beyond meeting minutes. Victoria Ellis’s words in 40point font. Significant reduction of undesirabs in high value corridors. The crowd murmurs. Video compilation plays. 23 incidents. Same officers. Same language. You don’t belong here. Move along. Jerome Washington testifies.

Sullivan pushed my cart. Said I lowered property values. Hayes dismissed my complaint. Said insufficient evidence. Three witnesses saw it. Nobody asked them. Kesha Daniels next. He said I was loitering at a bus stop. I had a pass. Showed it. He said I didn’t belong in this neighborhood. I’m black. The area is gentrifying.

What did he mean? Silence now. Everyone is listening. Brennan testifies. Place the manual on the table. Found in Hayes office. Effective community policing in high transition areas. Written 2014. Distributed to 23 officers without approval. She reads sections. Instructions to target homeless populations. Use neutral language. Minimize documentation.

Exercise body camera discretion. Hughes looks at Hayes. Captain, did you write this? Hayes sits in full uniform. Lawyer beside him. That document was internal guidance taken out of context. Did you write it? Yes or no? Yes. Chambers erupt. Hughes gavvels silence. Sullivan testifies. Ellis and union attorney flanking him.

Officer Sullivan, why did you pour coffee on Detective Bennett? Sullivan’s voice shakes. I thought he was homeless. He looked. He smelled. People complained. I was doing my job. Assaulting people is your job. No, I was trained to. He stops. Trained to what? Sullivan looks at Ellis. She nods.

Trained to remove undesirabs from high value areas. The words echo. Who trained you? officers Okconor, Douglas, Turner, they said we were cleaning the streets, making the city better. Give me the manual and the coffee. He wasn’t moving. He argued. I wanted him gone. So, you assaulted him? Yes. Would it matter if he was just homeless? Would that make it acceptable? Sullivan doesn’t answer.

Hughes turns to Bennett. Detective, you’ve heard this testimony. Anything to add? Bennett walks to the microphone. No notes needed. I’m a decorated detective, father of two, 12 years of service. Sullivan treated me like garbage because of how I looked. His voice is steady, quiet, powerful. But I had a badge. I could prove who I was.

The 47 others on that spreadsheet couldn’t. That’s the system. If you prove you belong, maybe you get respect. If you can’t, someone crushes your breakfast and tells you you’re the problem. He pauses, looks at Sullivan. Am I undesirable? Sullivan won’t meet his eyes. Absolute silence. Hughes calls the vote. Seven hands raise. Independent investigation.

Terminate B partnership, reform internal affairs, suspend all officers pending review unanimous. The crowd erupts in applause, but Bennett doesn’t celebrate. Melissa Mitchell is still missing. 14 other girls are still gone. April 3rd, Inspector General Diane Foster announces the results. Sullivan fired, criminal charges filed, assault, civil rights violations, loses pension eligibility, but Okconor Douglas Turner, forced retirement, full pensions, union protections. Hayes resigned. No criminal charges. Two weeks later, the Business

Improvement District hires him as security consultant. Salary 180,000, double his police chief pay. Victoria Ellis, no charges. B partnership was legal. Manual destroyed officially, but copies love online forever. The system bent. Didn’t break. Bennett can’t return to undercover work.

His face is public now. Narcotics reassigns him to the training division. Brennan gets promoted. Captain, reformed internal affairs division. First case, reviewing 15 years of dismissed complaints. The 14 girls from Operation Crosswire remain missing. The FBI takes over the investigation. No arrests yet, but Carol Mitchell’s daughter, Melissa, number 15, was found in Ohio 3 weeks after the hearing. Alive. Rescued during a federal raid on a different trafficking ring.

One out of 15. Bennett runs through Riverside Park again. Early morning, same bench where it started. No one stops him. A young officer drives past. Slow. Their eyes meet through the window. The officer nods. Respectful. Keep driving. Small change. Not enough, but something. Bennett thinks about Sullivan’s boot crushing that hot dog. About the coffee.

About Maya asking, “Did he say sorry?” No, baby. He never did. But 47 people don’t have to stay silent anymore. Complaint number 48 won’t be dismissed. And maybe, possibly, the next person on a bench eating breakfast won’t be treated like garbage. They trained him to remove undesirabs. He just didn’t know one of them wore a badge. And that badge changed everything.

If this story matters to you, share it. Systems change when silence ends. What’s the real cost of cleaning up your city? Who decides who belongs? Drop your thoughts in the comments and subscribe because some stories need to be told even when powerful people don’t want you to hear

News

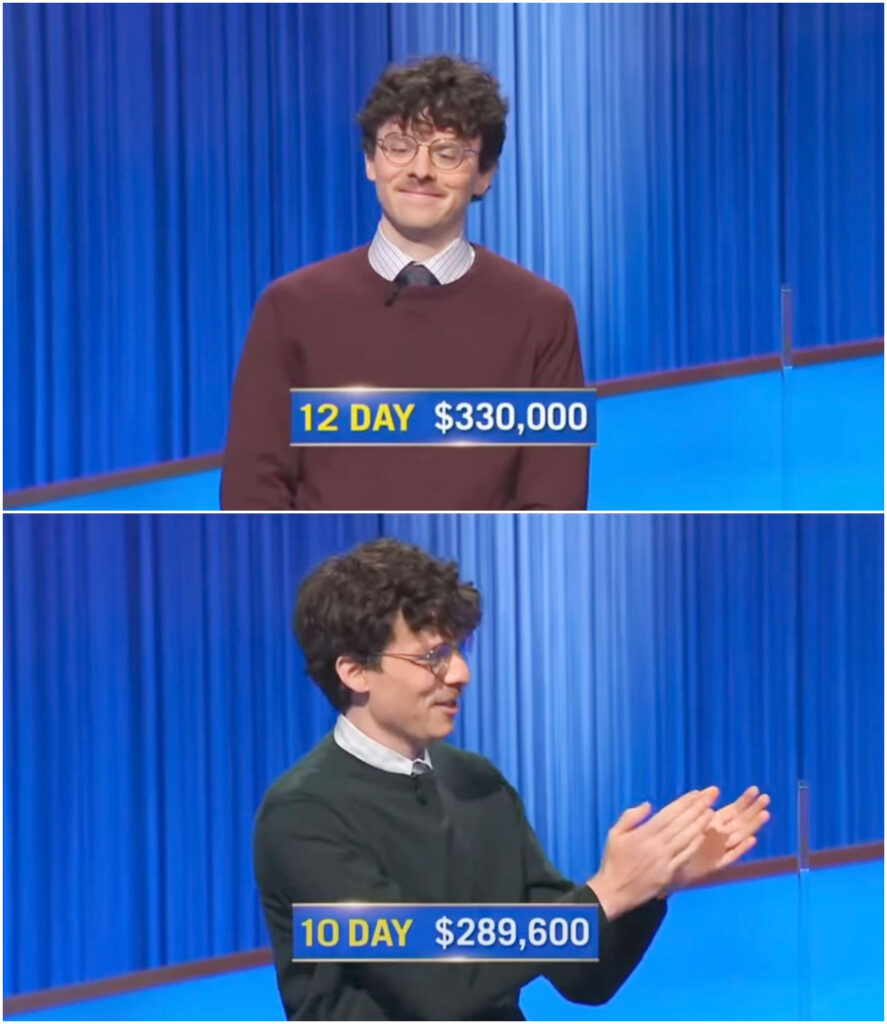

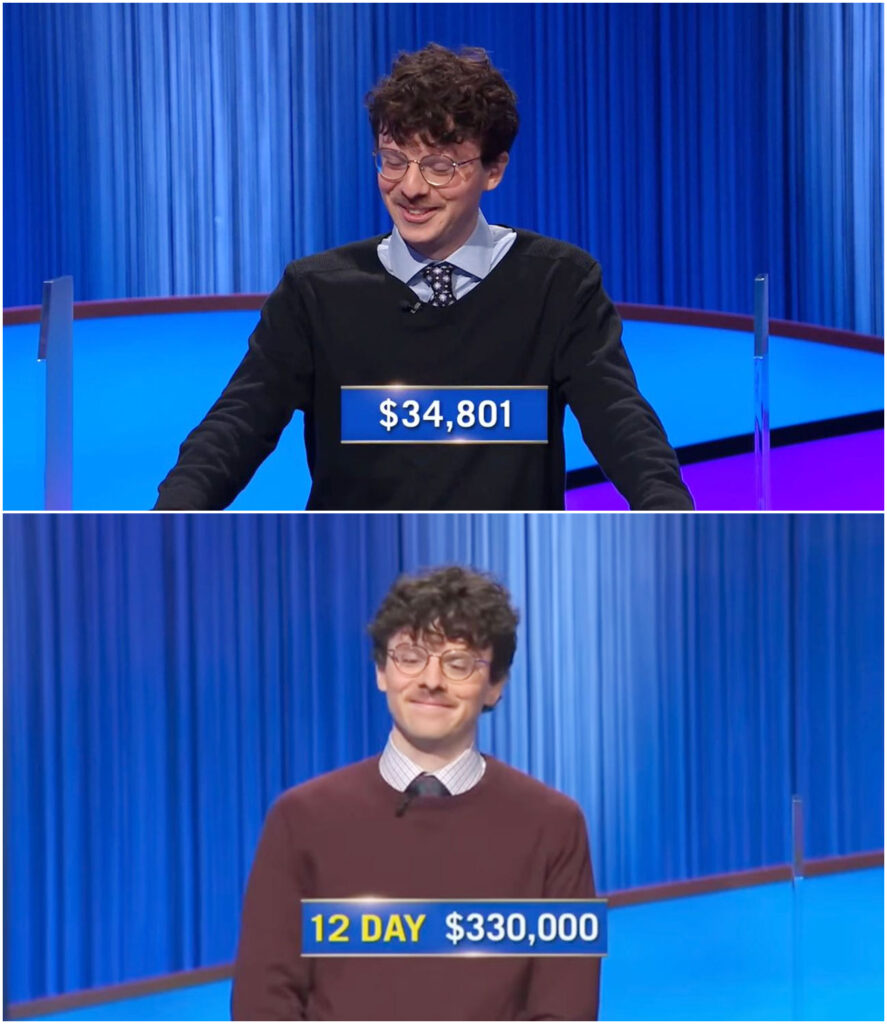

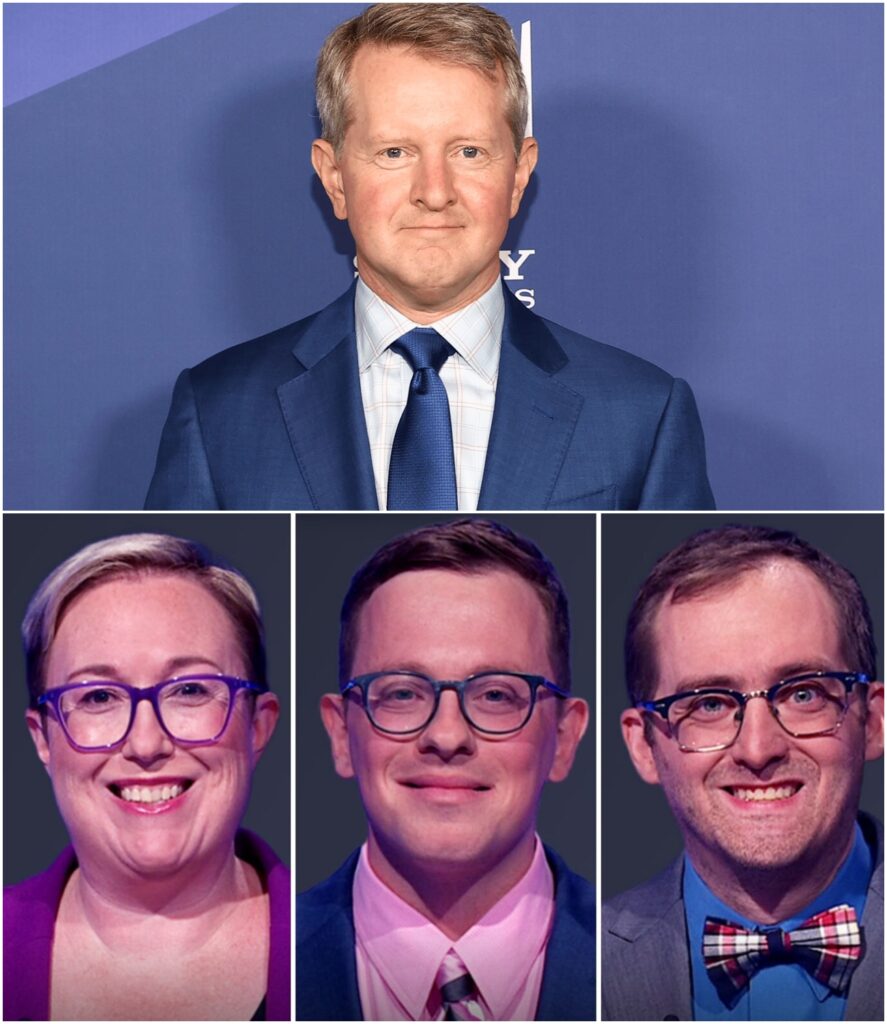

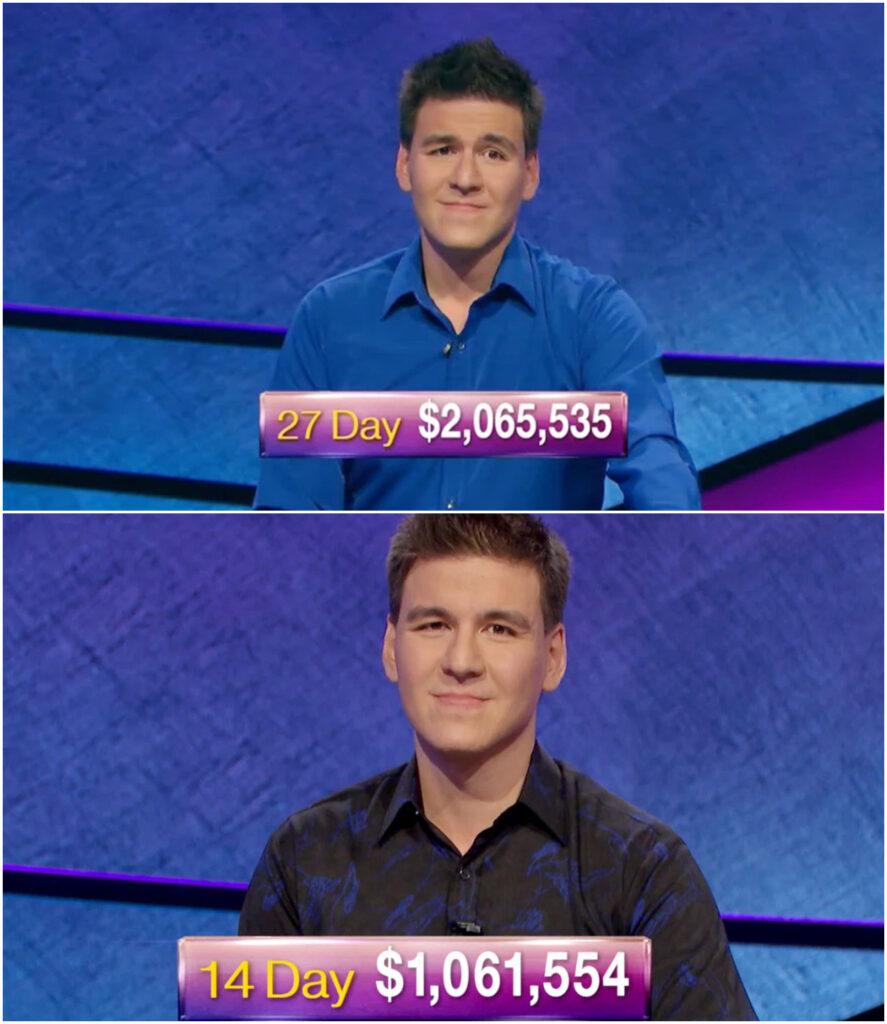

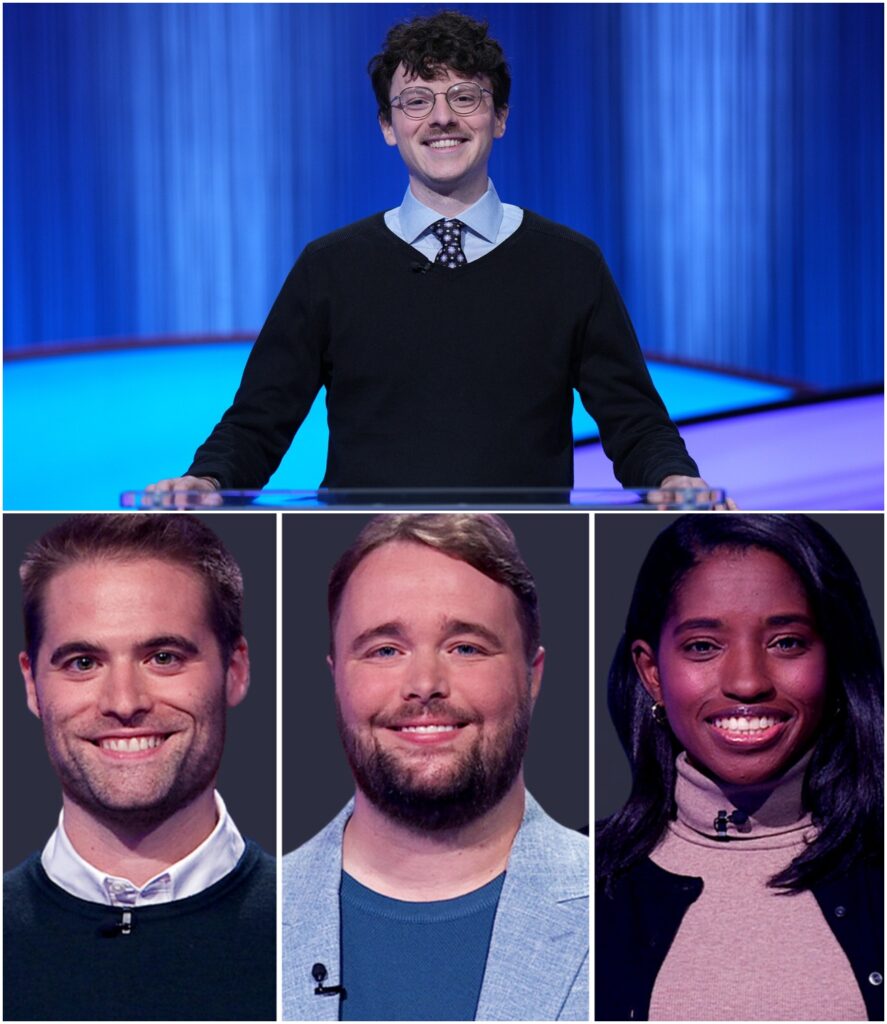

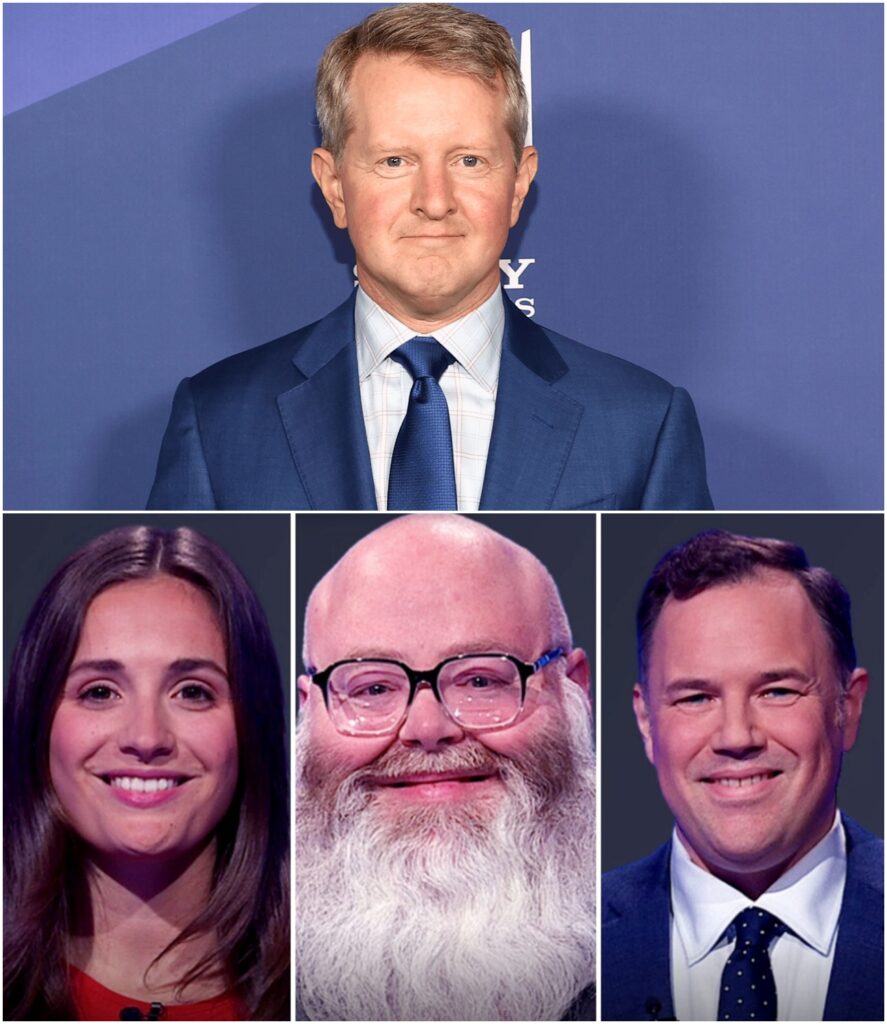

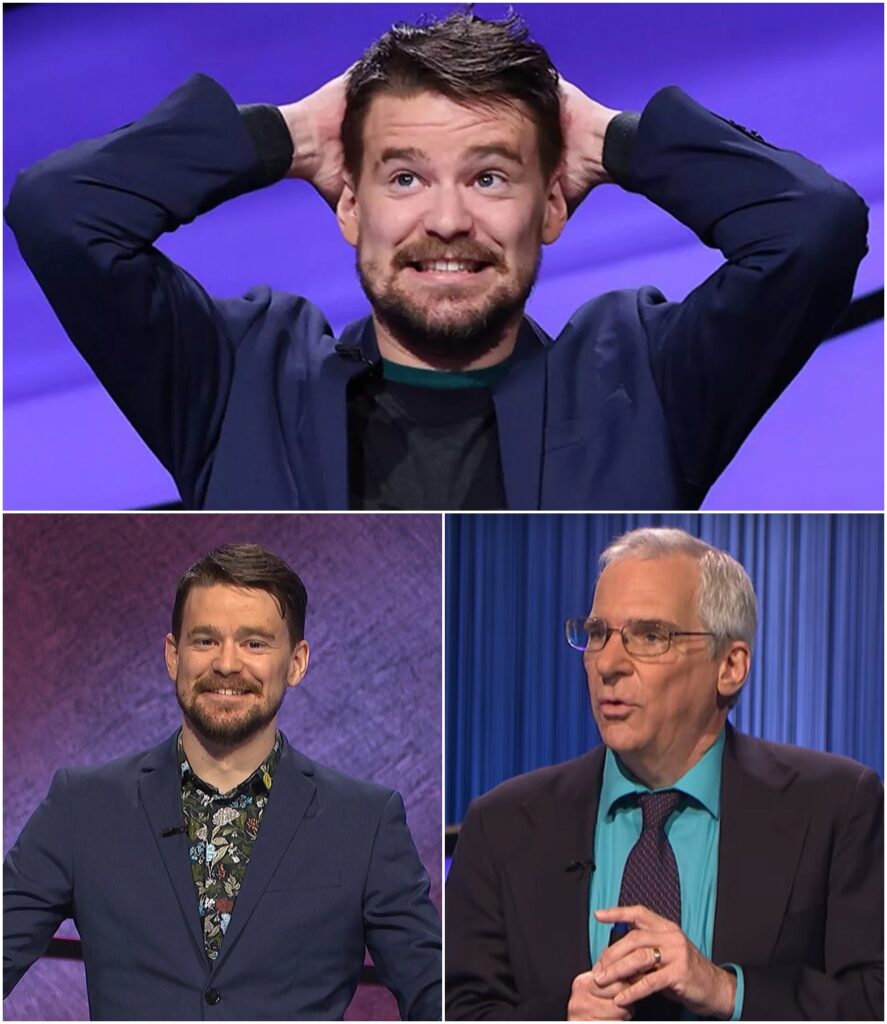

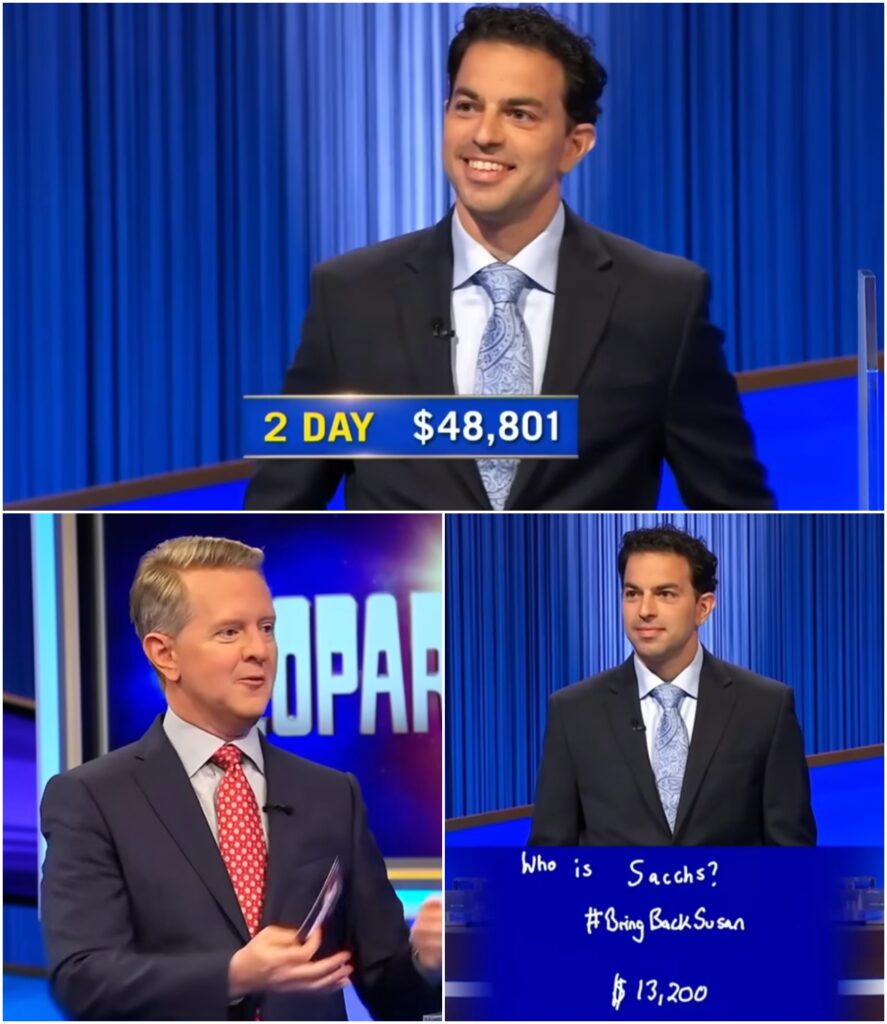

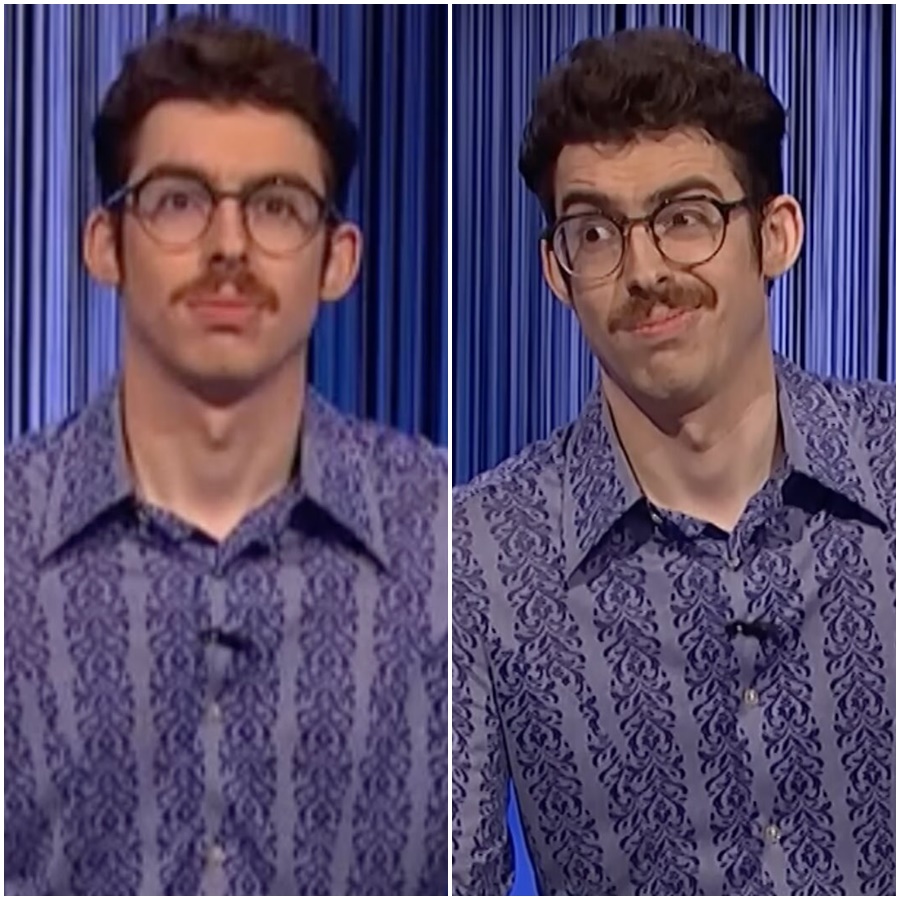

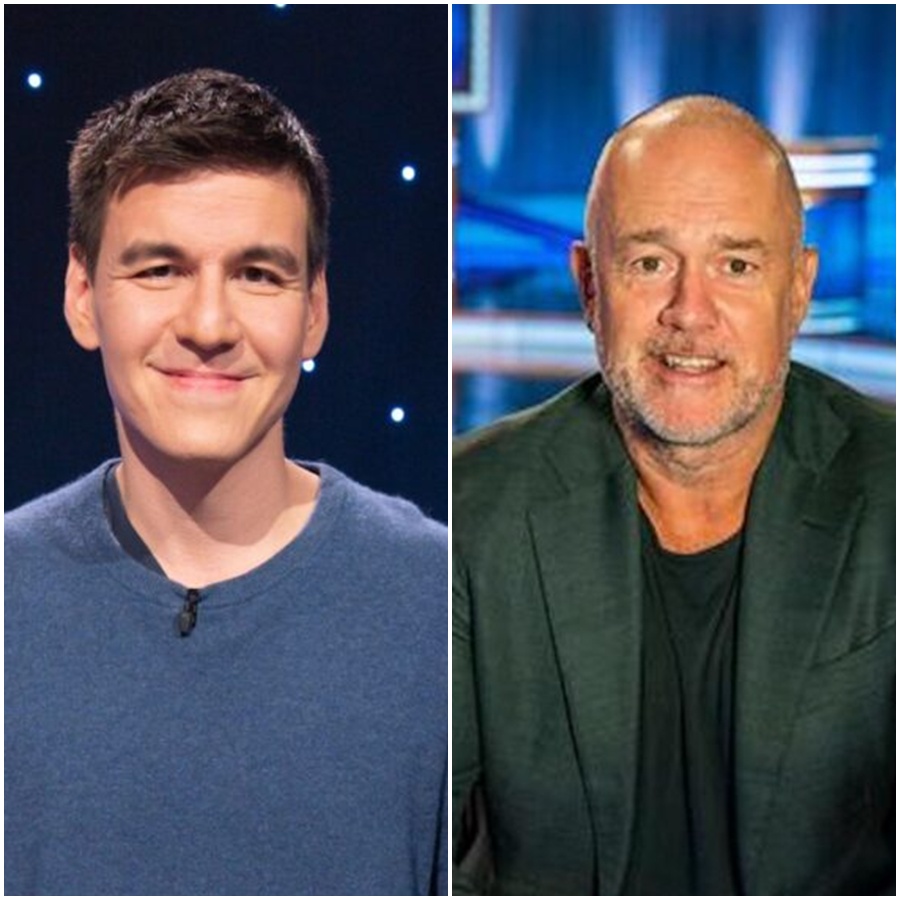

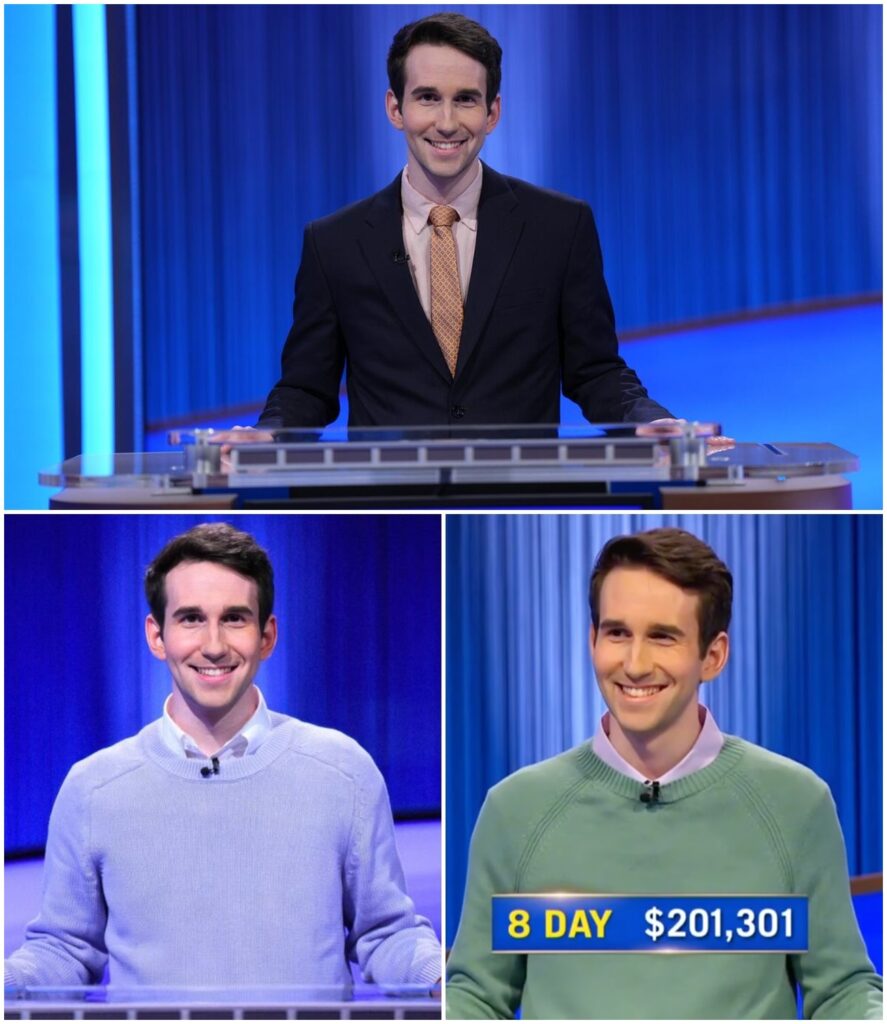

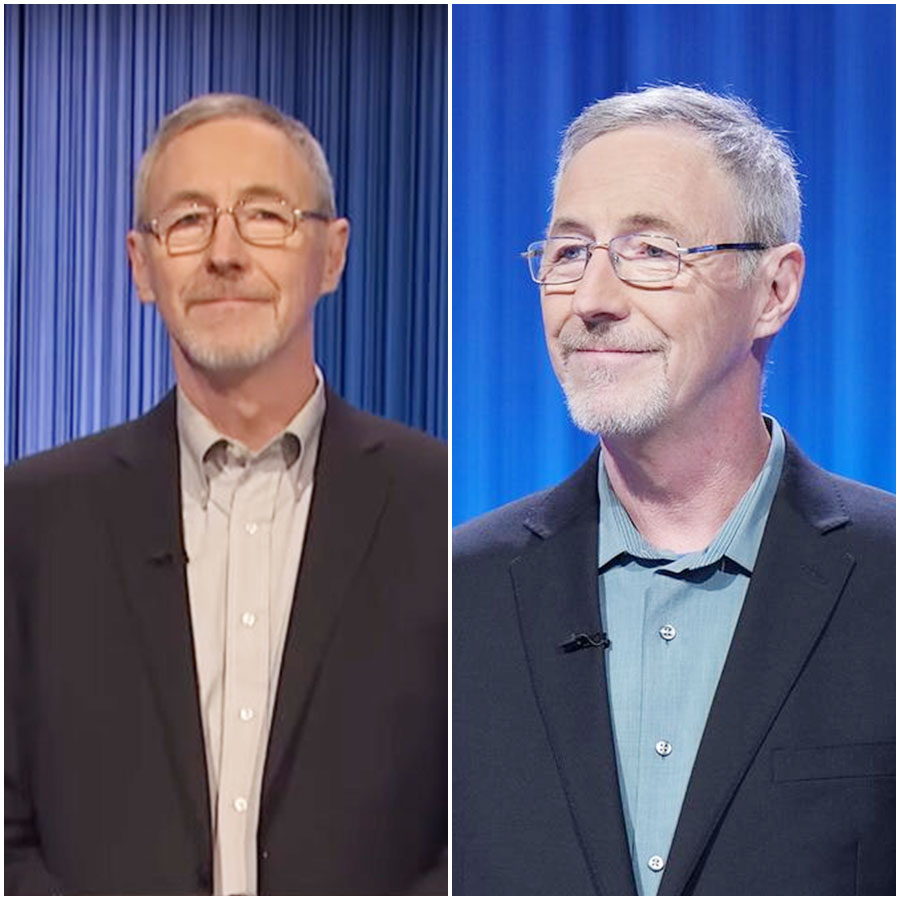

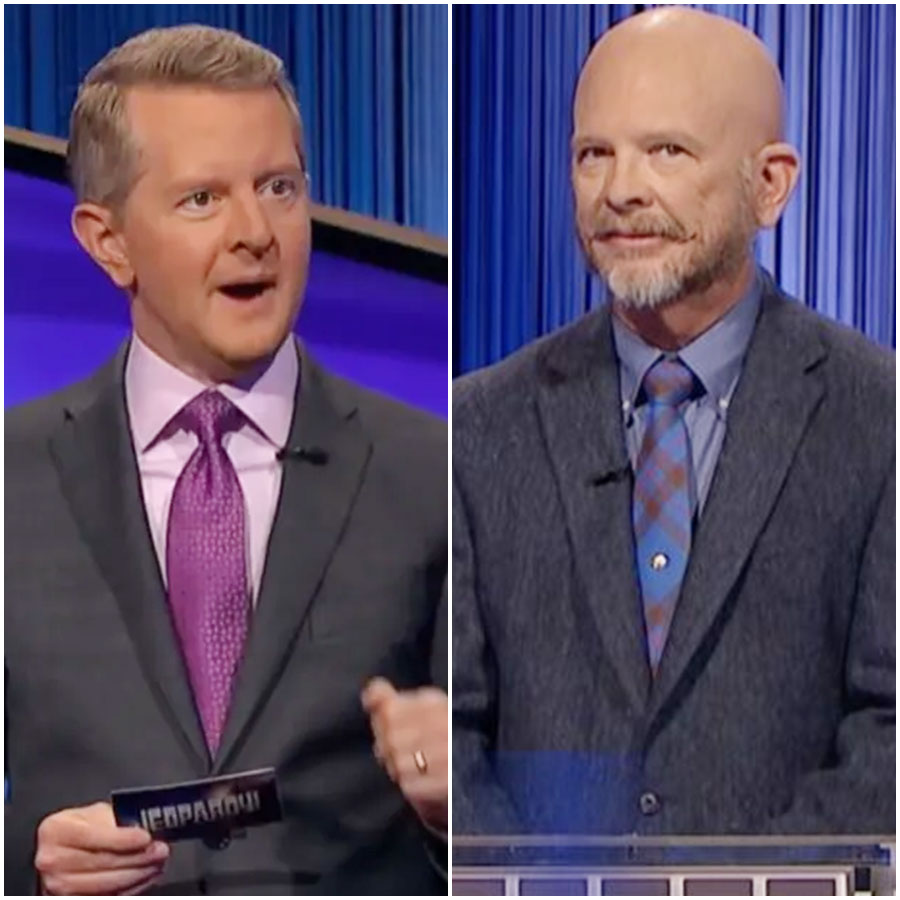

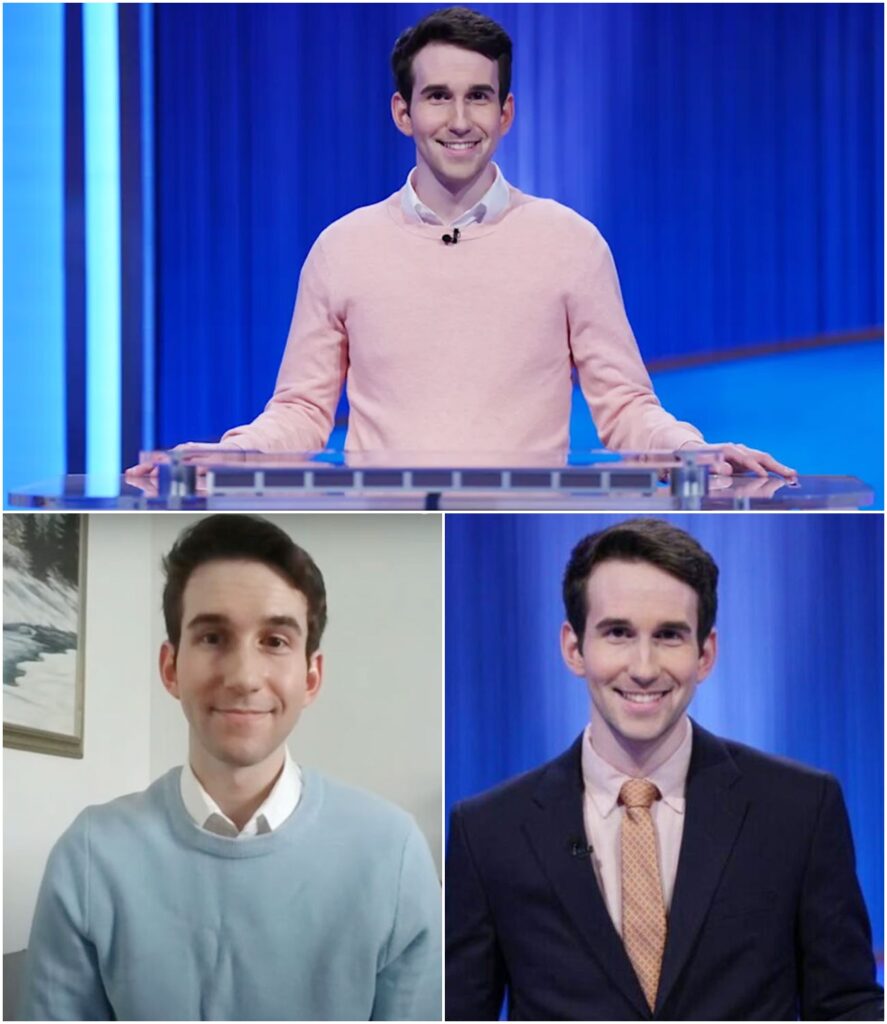

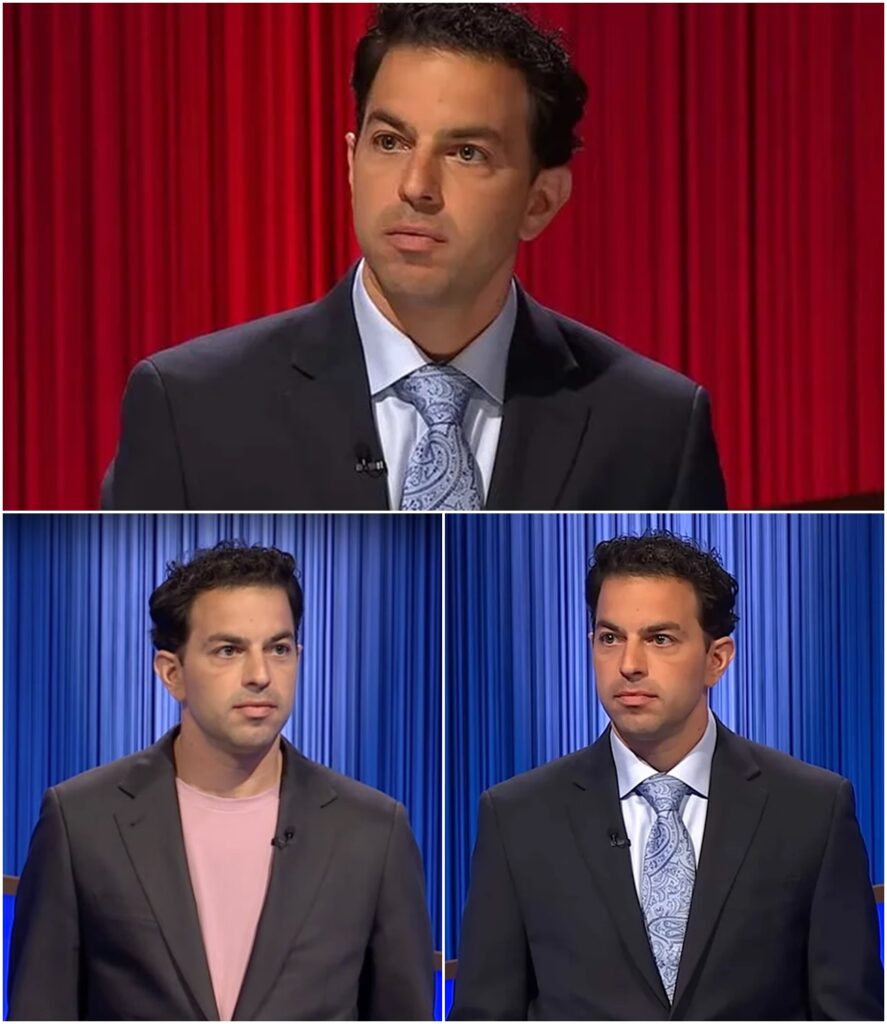

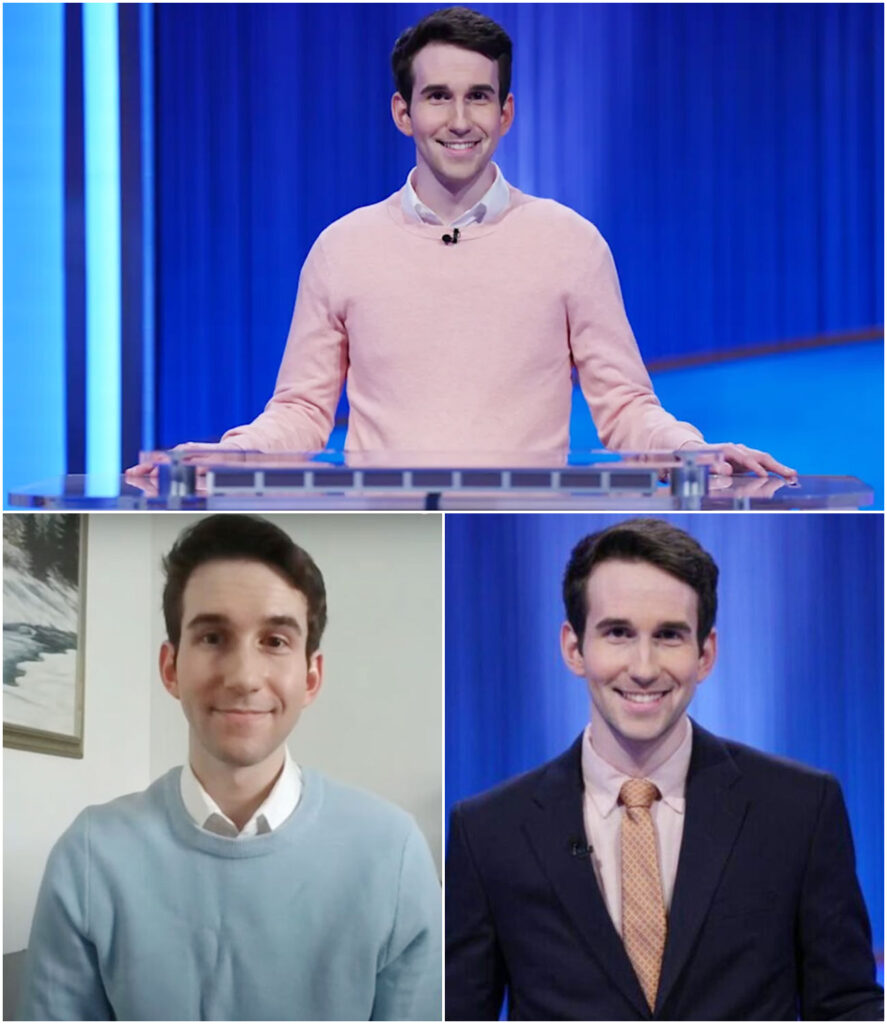

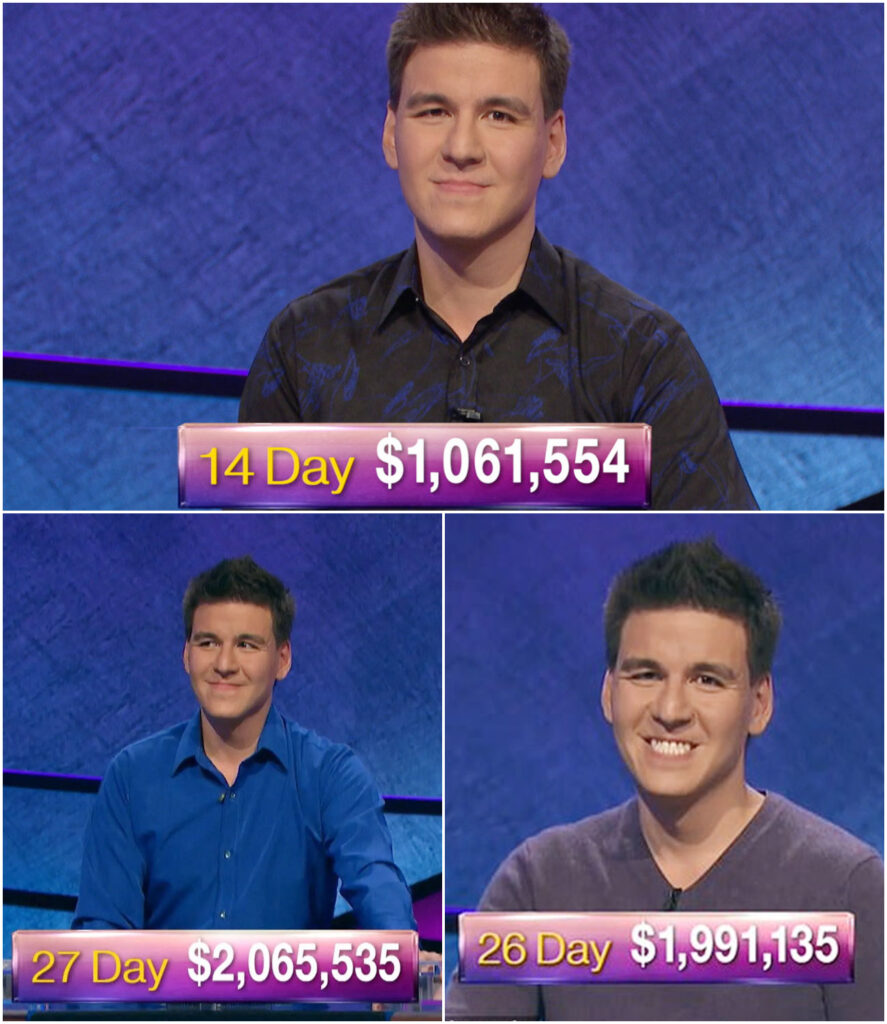

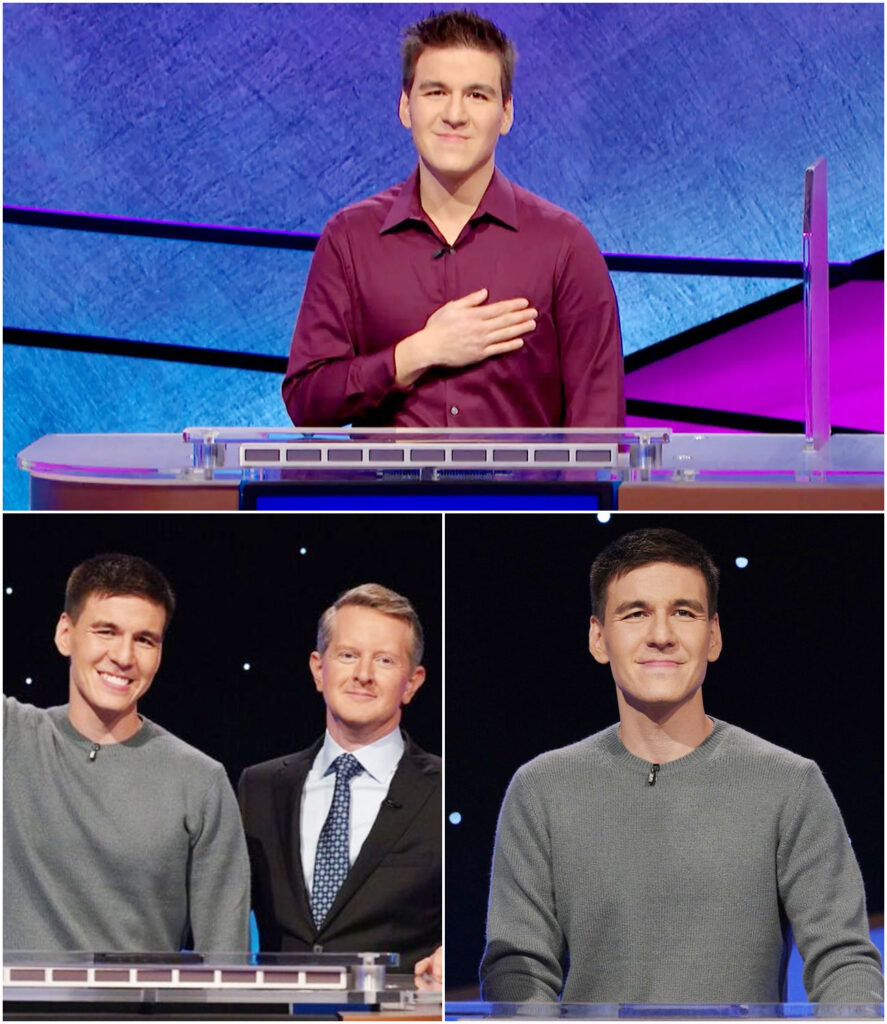

Double The Danger! Ron Lalonde Follows His Twin Brother Ray As A ‘Jeopardy!’ Champ: Did He Secretly Eclipse His Brother’s Eye-Watering Earnings Record?

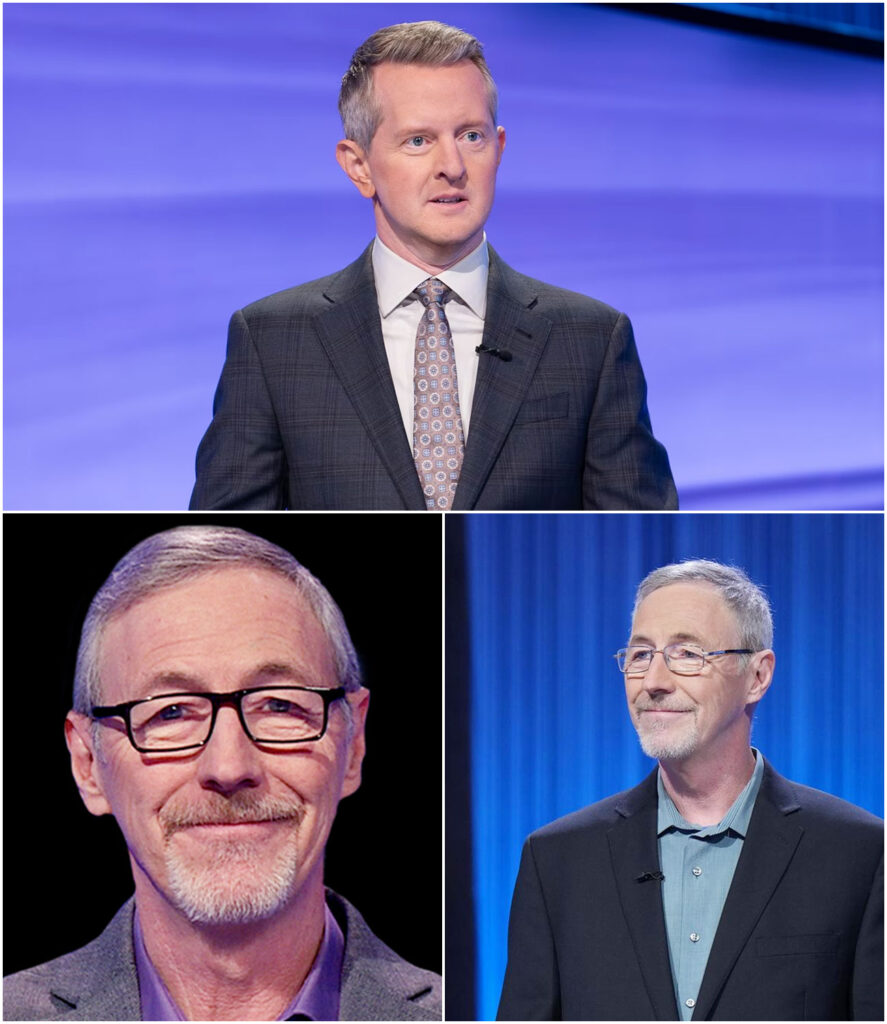

Ron Lalonde follows twin brother as Jeopardy! champion with eye-watering earnings Twin brothers Ron and Ray Lalonde both became Jeopardy! Champs, while Harrison Whitaker’s 14-game streak ended View 3 Images Ron Lalonde has followed his twin brother Ron Lalonde followed in his twin brother’s footsteps this week by becoming a two-day Jeopardy! champion, echoing the […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Fans Complain They Don’t Like Celebrity Video Questions

‘Jeopardy!’ Fans Complain They Don’t Like Celebrity Video Questions Courtesy of ‘Jeopardy!’/YouTube Courtesy of ‘Jeopardy!’/YouTube What To Know Jeopardy! has recently featured celebrity video clues in some episodes, often as a way to promote upcoming releases or tie into themed categories. Many fans have expressed frustration on social media, arguing that these video clues disrupt the […]

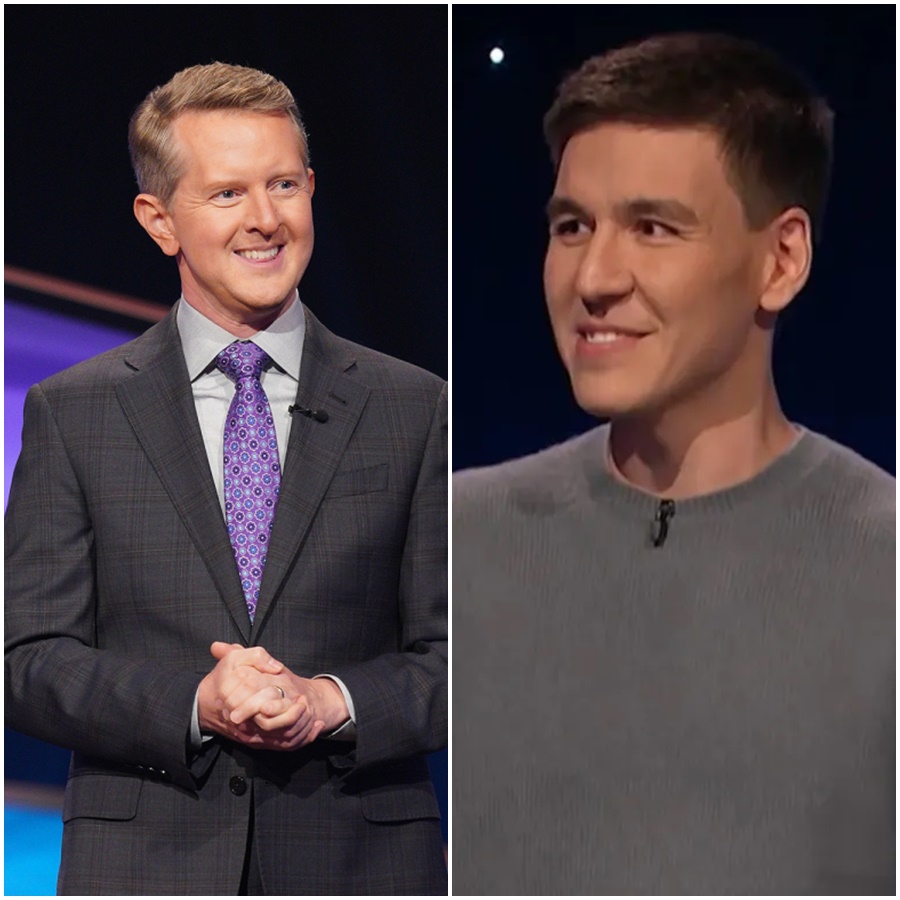

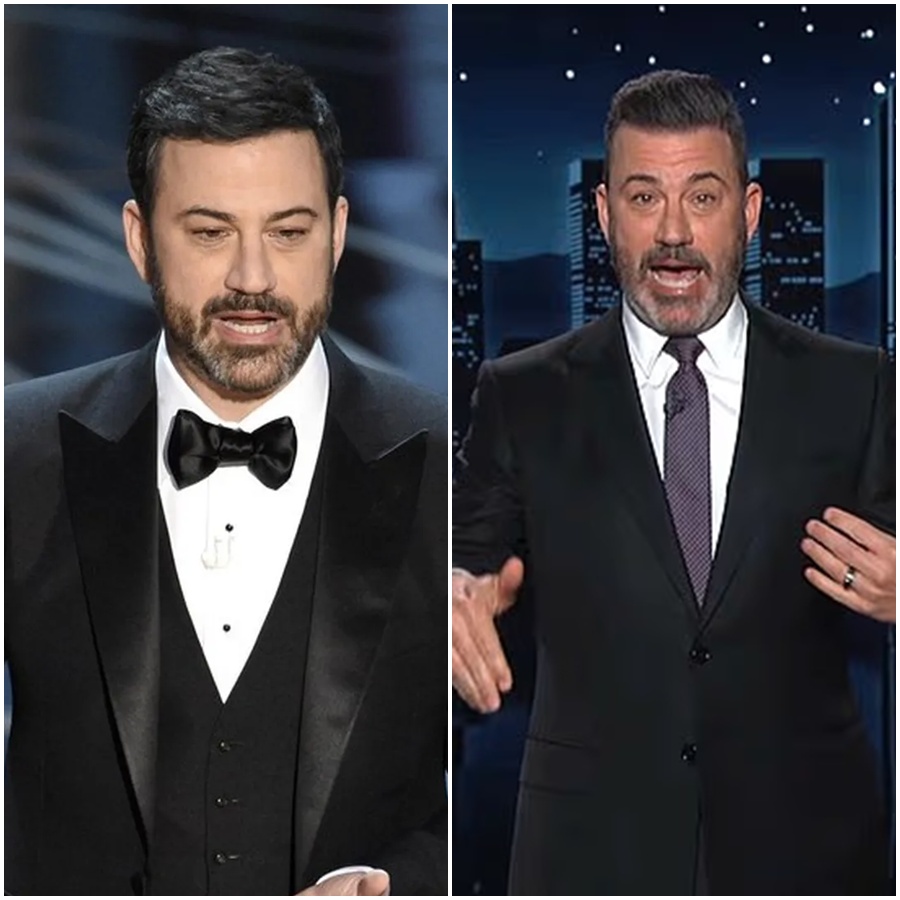

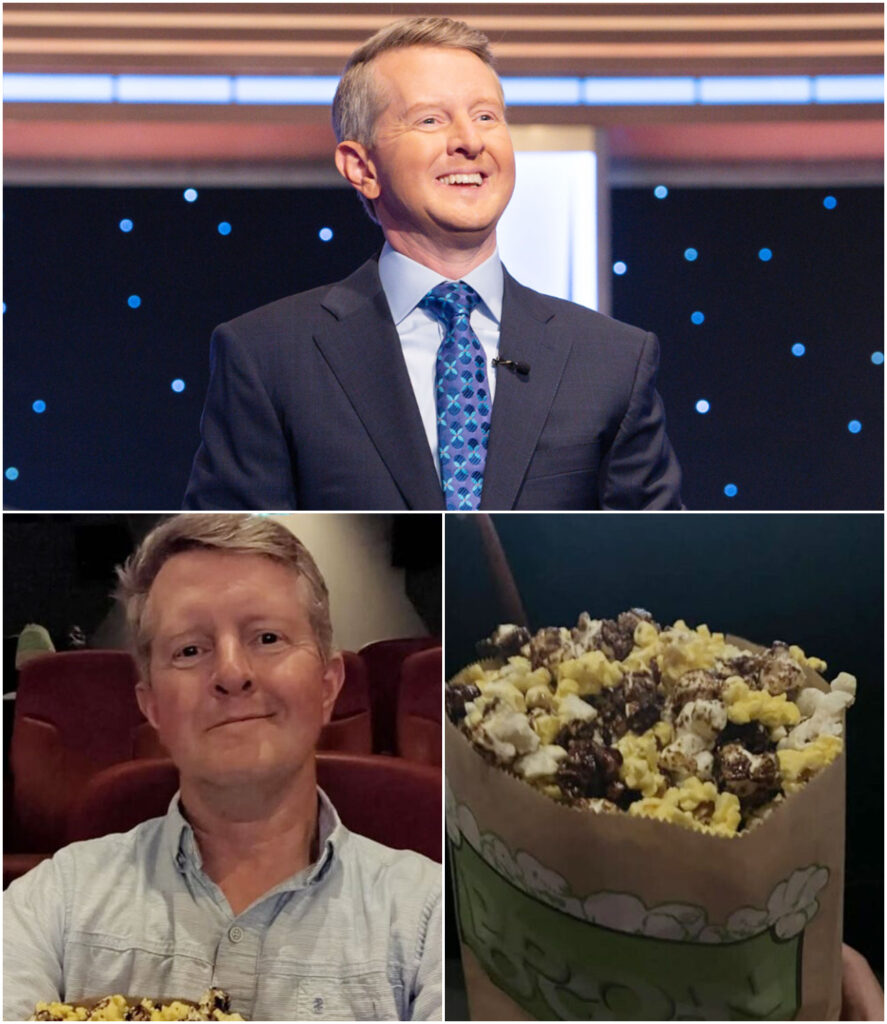

3 times Ken Jennings has apologized on behalf of Jeopardy! and his actions

3 times Ken Jennings has apologized on behalf of Jeopardy! and his actions Ken Jennings is beloved for many reasons, and one of them is because the TV personality seems to know how to take accountability when it’s time whether it’s for him or Jeopardy! Jeopardy! host Ken Jennings isn’t too big to admit he’s […]

Jeopardy! fans slam ‘nonsense’ clues as one category is ‘the worst’

Jeopardy! fans slam ‘nonsense’ clues as one category is ‘the worst’ During the latest episode of Jeopardy!, viewers were outraged over one vocabulary category in the first round that had three clues which stumped all of the contestants View 3 Images Jeopardy! fans slam “nonsense” clues as one category is “the worst”(Image: Jeopardy!) Jeopardy! fans […]

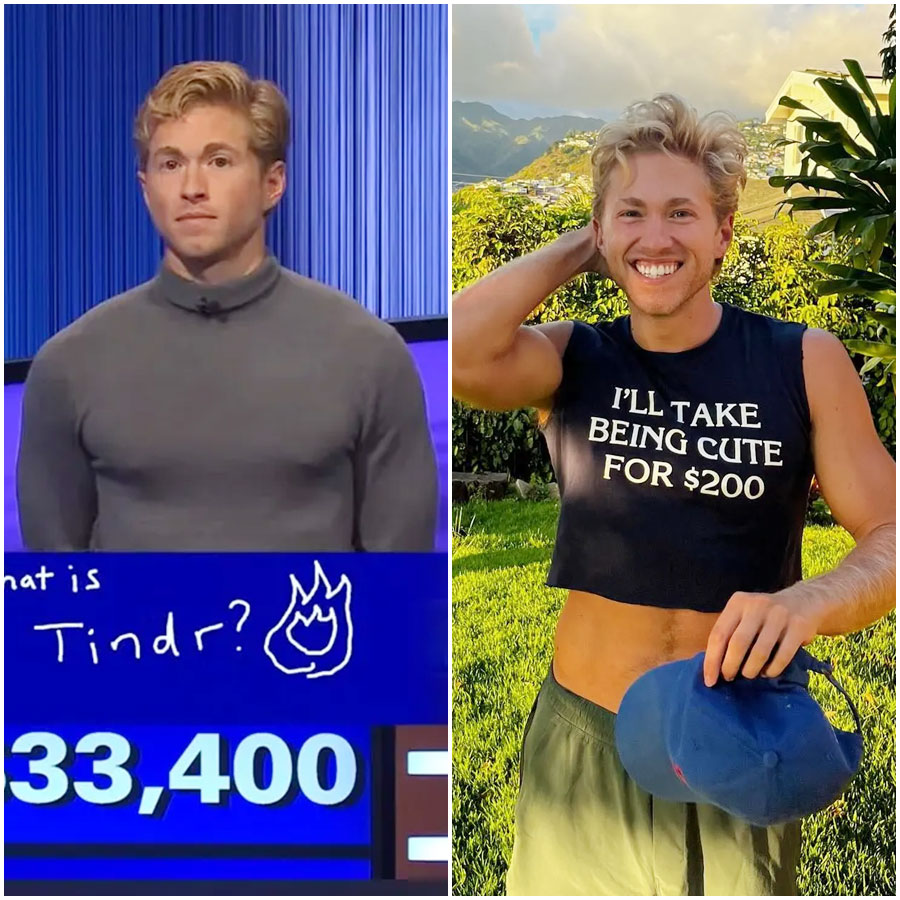

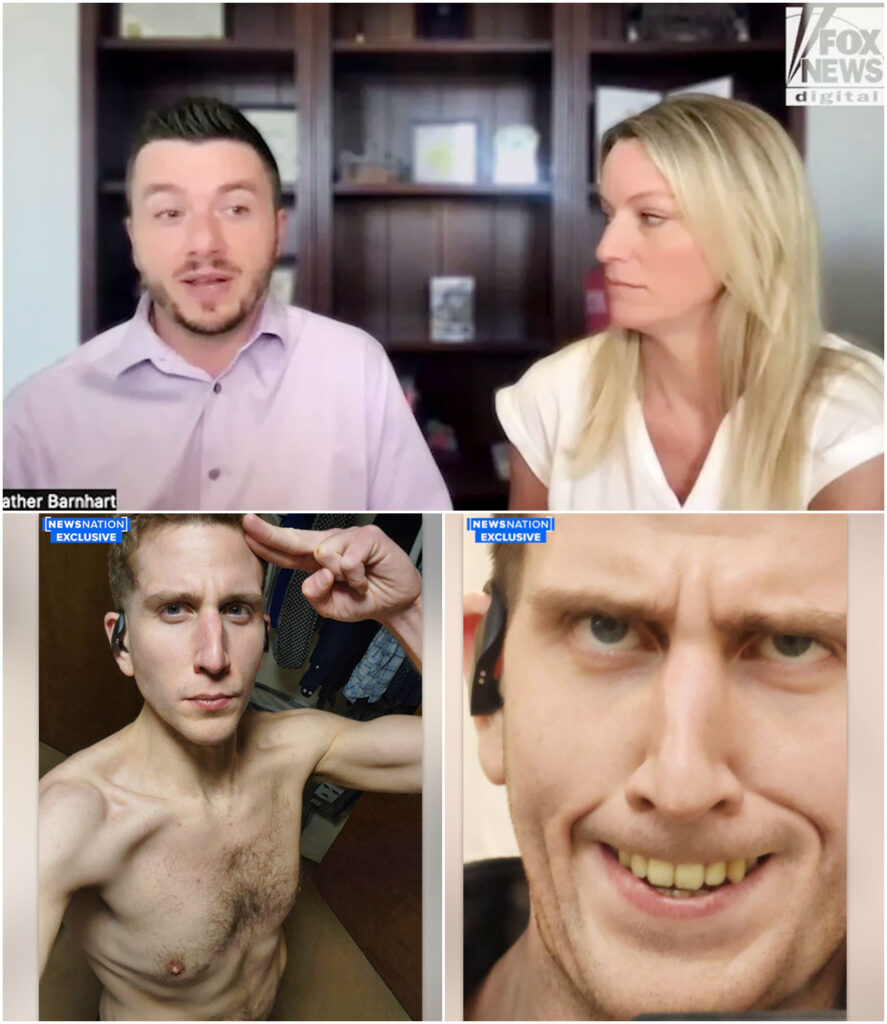

‘Jeopardy!’ Champion Arrested on Felony ‘Peeping’ Charges

‘Jeopardy!’ Champion Arrested on Felony ‘Peeping’ Charges Jeopardy, Inc! Two-day Jeopardy! champion Philip Joseph “Joey” DeSena, who appeared on the long-running game show last November, was arrested on Monday, December 1, on two felony “peeping” charges. According to MyFox8.com, citing a warrant filed by the Currituck County Sheriff’s Office in North Carolina, DeSena is accused of installing cameras in a […]

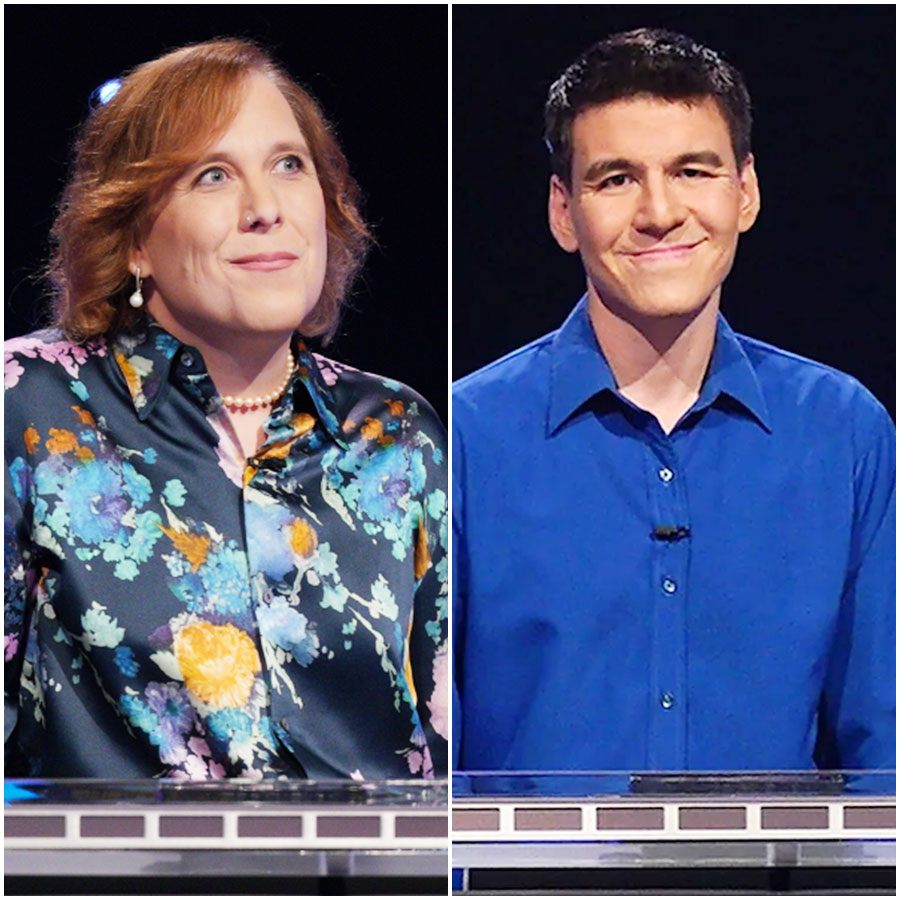

‘Jeopardy!’ Contestant Reveals She Got Death Threats After Beating Ken Jennings Sony/Jeopardy! When you defeat a 74-game Jeopardy! champion, you’re expecting cheers and a pat on the back. However, Nancy Zerg received death threats for six months after winning her game against Ken Jennings. Zerg, now 69, has revealed in a new interview how her life was made hell after […]

End of content

No more pages to load