He Played Tonto, Now The Truth Of Jay Silverheels Comes To Light

I will take the name Mexican enemies have given me. The whites will learn it and you will earn it. Jay Silverhills made history as the first Native American to play a native character on TV. He became famous as Tanto in The Lone Ranger. But behind the scenes, something was very wrong. In 1957, when someone asked him about his most famous role, he said just three words. Tonto is stupid.

That wasn’t the only secret. He was paid half of what his white co-star earned. A director once tried to physically attack him on set, and the name Tonto itself meant something he could never escape. Today, we’re uncovering what really happened to the man who smiled on camera but suffered in silence. J. Silverhills was born Harold J.

Smith on May 26th, 1912 on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve near Hagersville, Ontario. He came from a large Mohawk family, one of at least 10 kids crammed into a small house. His father, Alexander George Edwin Smith, was a Kauga war hero who earned the military cross in World War I for bravery at the S and ERA.

But after the war, he came home damaged, deafened by artillery, stuck on a farm, and surviving on just $49 a month from the Canadian government. His war medals didn’t feed the family. His injuries never went away. Harold saw him suffer headaches and hearing loss every day. His mother, Mabel, was part Mohawk, part Senica, and carried the weight of keeping the house running.

She used traditional medicine because doctors wouldn’t see them. They couldn’t afford much, and what little they had came from the land, trade, or herbal knowledge. Poverty wrapped around their lives from the start. By age five, Harold was already showing signs of athletic talent, racing around in local lacrosse matches on the reserve.

By 19, he was playing box lacrosse professionally for the Toronto Teumps under the name Harry Smith. He didn’t go alone. His cousins and brothers, Porky, Beef, and Chubby, were right there with him, traveling through Buffalo, Rochester, Atlantic City, and beyond. They played nearly non-stop through the 1930s, earning money, dodging poverty, and building a name.

That name became Silver Heels, given to Harold after he sprinted past a defender so quickly it looked like his shoes flashed silver. It stuck. Newspapers picked it up. Fans showed up just to see him run. One season, he scored more than four goals a game, and coaches started assigning two men just to guard him. But athletic fame didn’t mean freedom from the system.

Harold grew up while Canada’s residential schools tried to erase indigenous languages. At Six Nations, students were beaten for speaking Mohawk. Some were fed soap or strapped. Harold’s own sister was sent away to a residential school and came back unable to speak her own language properly. Families were torn apart by policies that banned ceremonies, punished their spirituality, and pushed them into silence.

Officials called them lazy. They said they lacked the ability to compete. That message lingered not just in reports, but in everyday life, in how people looked at them, talked about them, treated them. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, Harold’s family, like many others, sank deeper. They moved to Buffalo.

Harold worked odd jobs, labored on farms, did whatever it took. His father, despite being a decorated veteran, could barely move without pain. His mother bartered away family heirlooms to get food. Government rations were often spoiled. Harold saw his parents give up everything just to keep the lights on. That kind of poverty didn’t just hurt the stomach.

It made people feel like they didn’t exist. Still, Harold pushed forward. His speed on the lacrosse field opened doors. In 1932, he went pro and played for money, $75 per game, big cash during the depression. In one game in Montreal, a rough foul sparked a brawl and Harold threw punches that got him suspended. But when he came back, ticket sales tripled.

People wanted to see him, even if it meant controversy. He made headlines. He kept going. Then came boxing. Harold fought as a middleweight in the Golden Gloves tournament at Madison Square Garden. He made it to the semifinals before taking a brutal punch that broke his jaw in two places. The injury ended his boxing dreams, but the prize money kept him afloat.

He lost nearly 25 lbs on a liquid diet, but he didn’t quit. That fight taught him how to take pain and keep moving. In 1937, he toured Los Angeles with his lacrosse team. One day, while sprinting at Gilmore Stadium, comedian Joe E. Brown noticed him and offered a small film role. Harold performed a stunt, a diving catch that took 11 takes to get right.

He was paid $150. That was twice what lacrosse paid. From there, things shifted. He got a Screen Actors Guild card, started calling himself Jay Silver heels, and by the end of the year, he’d appeared in five films. He wasn’t a star, but he was in. Hollywood didn’t roll out a red carpet. He worked as a stunt man, earning less than $20 a day and bust tables at night to survive, but in 1939, he landed a real role in drums along the Mohawk.

It paid $350 a week, more than he’d ever made. Studios liked the name Silver Heels. They told him to use it officially, said it sounded exotic. He took on small roles, mostly playing unnamed Indians. Casting directors made him strip to the waist like he was on display. They judged his body more than his acting. Still, he showed up, learned his lines, and kept getting work.

In 1941, he finally had a speaking role. By then he’d been in more than 15 films, usually uncredited, playing Indian scout or warrior number two. But he never gave up. He studied Shakespeare because a friend said, “If you can read this, you can read anything.” He didn’t think it was for him at first, but he learned. He served in World War II, though records are thin.

In 1945, he returned to Hollywood with a new name, J. Silvers. But the industry hadn’t changed. Native actors were still pushed aside for white actors in makeup. Roles were few and the ones that existed were insulting. In 1946, he auditioned for Captain from Castile, starving himself so his suit would fit. The director made him take off his shirt like usual.

It was humiliating, but he got the part. The film flopped financially, but he had a job. Still, he stayed uncredited even when he had lines. He traveled across the South with his lacrosse team where racism was loud and inescapable. Hotels turned him away. Restaurants wouldn’t serve him. He slept on buses while his white teammates got rooms.

Once in Louisville, police threatened him just for using a bathroom marked whites only. These weren’t rare events. They were constant. That’s why later in life when he finally had a platform in Hollywood, he used it to fight for better roles and representation. A decade passed before anyone really noticed him.

That changed in 1948 when director John Houston cast him in Key Largo alongside Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Beall. Jay played Tom Ociola, a seminal fugitive. Finally, a credited role in a major studio film. They shot it on the Warner Brothers back lot in Burbank for 78 days, building Florida in a controlled environment to keep costs low.

But for Jay, it meant climbing out of the shadows. No longer just another name lost in the credits. Two years later, in 1950, Jay was cast in Broken Arrow, a western that claimed to be progressive but couldn’t quite let go of old habits. He played Geronimo, a strong role, but not the lead. That went to Jeff Chandler, a white actor from Brooklyn wearing dark makeup to portray Coochis.

Even in a film that tried to present Native Americans more fairly, Hollywood couldn’t bring itself to let native actors lead. Real Apache people were hired as background extras from the Fort Apache reservation. Jay, a Canadian Mohawk, gave Geronimo dignity, but the contradiction wasn’t lost on anyone. Then came the moment that changed his life and TV history.

In 1949, when the Lone Ranger came to ABC, Silvers beat out 35 other actors to become Tonto. It aired on September 15th. For the first time, a Native American played a Native American character on television. For two decades, the radio version of Tanto had been voiced by white men like John Todd and Roland Parker.

Even when TV producers considered casting a native actor, they hesitated. One was fired for refusing to speak in broken English. They went back to John Todd before finally giving Jay the job. At the time, Hollywood’s standard was to paint Italian actors with Armenia bowl red clay to make them look native enough. Jay’s casting broke that mold.

He wasn’t supposed to win the part, but he did, and it changed everything. There was always a problem with the name. Tanto means fool or stupid in Spanish. Silver Hills knew it. He lived with it. Publicly, he smiled. Privately, he resented it. In 1957, during a visit to his home reserve in Ontario, someone asked him about his famous role.

His answer was quick. Tanto is stupid. That was all he said, just three words. But behind those words was a decade of quiet frustration. The name stuck through the decades, even as Native American groups pointed out its offensiveness. When Johnny Depp played Tanto in 2013, the controversy returned. Nothing had changed. And it wasn’t just the name.

Jay had a reputation for never reading his lines. Not because he was lazy, but because the lines were often bad, stiff, broken English written to sound authentic. So he’d adlib. He’d make it up. Me wait here. You go into town. That right. The phrases stuck. Directors were furious.

Alan Dinhardt remembered how one director, Wilhelm Tila, went red with rage and had to be physically held back from attacking Jay on set in 1955. But Clayton Moore, the Lone Ranger himself, defended his co-star. Let it play, he’d say. It sounds more natural. Jay had a point. He knew how people really spoke, but Hollywood didn’t want that.

They wanted a stereotype and he was forced to deliver it. Behind the scenes, things weren’t much better. The budget for each episode was only $12,500, so corners were cut. Jay and Moore didn’t even have proper dressing rooms in the beginning. They had to change clothes in a gas station restroom down the road. The heat on location was brutal, especially in Chadzsworth, where the suede and wool costumes turned into ovens. Jay had enough.

One day he refused to dress, just stood there waiting. Moore warned him that delaying the shoot could cost jobs, but Jay wouldn’t budge. The next day, private dressing rooms appeared. It was a small win, but it meant something. Jay could have just accepted the fame. He was a star now. The Lone Ranger was one of the top shows on TV.

It ranked number seven in Neielson ratings for the 1950-551 season and stayed in the top 30 for years. Over eight seasons, they made 221 episodes. But Jay never forgot the cost. He didn’t like what Tanto had become. He didn’t like being the sidekick who always spoke in broken sentences. He was fluent, articulate, sharp.

But the show didn’t let him be that. Then came a scare that stopped the show cold. In 1955, during a fight scene rehearsal, a stunt man fell onto Jay. Moore saw something was off. Jay was walking strangely. He followed him to the trailer and found him clutching his chest. Heart attack. Despite being an athlete, a lacrosse champion, a Golden Gloves boxer, Jay was a heavy smoker.

He missed eight weeks recovering. During that time, a new character, Dan Reed, was introduced to fill the gap. Writers explained Tanto’s absence by saying he was in Washington meeting the great white father. That line said more than they realized. At home, Jay was just Harold Smith. He married Mary Doma in 1945 and had four children with her, Jay Jr., Marilyn, Pamela, and Karen.

From his first marriage to Bobby Smith, he had two more, Steve and Gail. He joked about their mixed heritage. On the Tonight Show, he once said he married an Italian to get back at Christopher Columbus and called their kids indelens. But the joke hid something deeper. Jay’s grandfather had been a Mohawk Chief.

He grew up on the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario. Hollywood’s version of Indian was a long way from the truth he carried with him. In 1953, Jay Silverhills took on the role of Satanta, a Kaioa Chief in the film War Arrow. It wasn’t a lead role, but it placed him alongside big names like Morin O’Hara and Jeff Chandler.

Filming stretched from early March through April, shot across Arizona in places like Ngalas and Sonita’s Empire Ranch, plus a few scenes in California’s Agura. What started as a solid action western ended up being trimmed down by director George Sherman, who took out several action sequences and replaced them with talkie scenes that explained the action instead of showing it.

Even the studio admitted later this decision weakened the film. Still, it had strong stunt scenes and rich technicolor visuals. Morino O’Hara would later say Chandler was nice, but didn’t impress her as an actor. Silverhill’s character stood on the opposite side of the central conflict, a reminder of how native roles were usually placed, just outside the focus, but still present.

The following year, 1954, he played another supporting role in Drums Across the River. This time, he played TA in a western directed by Nathan Geran and starring Audi Murphy. It was shot in Technicolor in some of California’s most scenic spots, including Barton Flats and Red Rock Canyon. Murphy played a young man trying to stop a war with the Ute tribe while being accused of a crime he didn’t commit.

Silver Hill’s role wasn’t just background. His character represented the native voice in a story about land disputes and rising tensions. The film had intense horseback scenes, fights, and what one critic called a leap of death stunt that stood out. These kinds of physical scenes came naturally to Silverheels, who had once been a lacrosse player and boxer.

Morris Ankram joined him on screen as Chief Uray in a production that cost around a million dollars, a big budget at the time. After the Lone Ranger series wrapped in 1956 and stopped airing by 1957, Silver Hills returned as Tanto in two theatrical movies. First came the Lone Ranger in 1956, then The Lone Ranger and The Lost City of Gold in 1958.

The second film was 81 minutes long and shot in Eastman color by United Artists. He acted alongside Clayton Moore. Once again, the film did fine. Not a hit, but not a flop. What did hit hard was what came after. The role of Tanto had made him famous, but it also boxed him in. From that point on, most of what he got offered were similar native roles, often thin and stereotyped.

It was the kind of type casting that slowly dried up his options. In the 1960s, he kept showing up in westerns and TV guest spots. Wagon Train, Wanted, Dead or Alive, Rawhide, Laram, Daniel Boone, The Virginia, but almost always as the same kind of character. Even when he delivered solid performances, he rarely got the recognition or variety he deserved.

He was on Daniel Boone three times between 1964 and 1965, playing roles that barely gave him any dialogue. While filming The Lone Ranger, he earned about $100,000 per season, which would be around $850,000 today, but that was still just half of what Clayton Moore was making. That pay gap followed him through most of his career.

As the 1960s moved forward, so did the native rights movement. And with it came criticism, not from Hollywood, but from within native communities. Activists started calling out how native characters like Tanto reinforced old stereotypes. One scholar called tanto an Indian step-in fetch it while Russell Means a leader of the American Indian movement used tanto as an insult like how Uncle Tom was used in black communities.

Silver Hills found himself caught between the fame he’d earned and the image that fame was built on. He started to disappear from the screen not because he wanted to but because networks and studios got nervous about backlash. Even his past success couldn’t protect him from the changing climate. But instead of fading away or going silent, he turned towards something more lasting.

In the early 1960s, he co-founded the Indian Actors Workshop in Los Angeles. It started at the LA Indian Center with help from Buffy St. Marie, Iron Eyes Cody, and Rod Redwing. By 1966, it had become a real fixture, holding weekly classes and giving native actors a place to train, rehearse, and develop their skills. One of those future actors was Michael Horse, who later played Tonto in The Legend of the Lone Ranger in 1981 and became known for his role in Twin Peaks.

In 1973, Silver said their main goal was to unlock the dormant creativity inside native communities. He didn’t just say it, he built it. In the late 1930s, while working as a stunt man and background actor in Hollywood, Jay Silverhills married Bobby Smith. Their marriage fell apart by 1943. Around the same time, he was juggling unstable film work and military service during World War II.

He was often away performing dangerous stunts for films like The Seahawk and Western Union, earning barely enough to live on, just about $50 to $75 a week. The divorce left him estranged from his two children, Steve and a daughter whose name varies in records, sometimes listed as Gail and sometimes Sharon.

Jay’s limited income, constant travel, and the legal complications of wartime service made it nearly impossible for him to stay in close contact with them. A couple of years later, in 1945 or 1946, Jay married Mary Doma, an Italian-American woman he once joked about marrying just to get back at Christopher Columbus.

He called their kids Indelians. They had four children, Jay Jr., Marilyn, Pamela, and Karen, and settled down in Kenoga Park, California. In 1949, Jay landed the role that would define his public image, Tanto in The Lone Ranger. It brought him fame, but not fortune. Contracts back then didn’t offer much in the way of long-term pay, and being so deeply typ cast meant that Tanto was both a breakthrough and a trap.

Even after the show ended in 1957, he was constantly boxed into roles that looked and sounded like Tanto. He had a heart attack in 1955 while filming and missed eight weeks of work, which didn’t help his already strained finances. Still, he and Mary remained together until his death, navigating all the ups and downs of a long and unstable career.

By the early 1960s, he began thinking about how Native Americans were represented in Hollywood, and more importantly, who got to represent them. He started quietly supporting a project that would become formal in 1966, the Indian Actors Workshop. It was his way of doing something concrete instead of protesting from the outside.

He believed boycots wouldn’t work for Native Americans the way they had for African-Ameans, saying a boycott by Indians would not mean the loss of money that a negro boycott could bring. So he focused on what he could control, training. Alongside Noble Kid Chisel and William Basset, Jay taught acting, voice, stunt work, and even nutrition to aspiring native actors.

They held weekly sessions at places like the Los Angeles Indian Center and a Methodist church in Echo Park. The goal was clear, to help native actors get into the Screen Actors Guild, to land better roles, and to gradually shift how studios saw them. Not everyone appreciated this approach. Activists like Russell Means saw tonto as a symbol of everything wrong with native representation.

The character was mocked as an Indian step and fetch it and the word tonto even became a slur in activist circles. But Jay stuck to his path. He believed that real change would come not from yelling at the gates but from getting people through them. He even ran a letterw writing campaign to President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, and top TV executives, urging better portrayals of Native Americans on screen.

The workshop also tackled broader community issues like alcohol abuse, and care for the elderly. It wasn’t just about acting. It was about identity, pride, and survival. As the 1970s rolled in, Jay took on a second career, harness racing. He earned a provisional driver’s license in 1974 and trained horses at Hollywood Park. He enjoyed jogging them around the track and his fame helped promote races when he went on tour back east in 1973 and 1974.

One of the horses he was later honored with, Hiho Silver heels, broke a track record at Los Alamitos in 1996. Jay’s widow Mary and son Jay Jr. were there to witness it. But by then, Jay had long been gone. In 1975, just as more serious and dignified roles were finally coming his way, he suffered a series of strokes that left him partially paralyzed.

In 1976, another major stroke severely affected his speech. On July 17th, 1979, just months before his death, he received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He attended in a wheelchair surrounded by native dancers. He could barely mumble a few words of thanks. It was a quiet, bittersweet moment for a man who had spoken so loudly with his actions.

On March 5th, 1980, Jay died at age 67 from complications of that stroke and pneumonia at a hospital in Calabasas. He was cremated and his ashes were returned to the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario where he was born. His son J. Silverhills Jr. picked up the family mantle and pursued acting. He appeared in The Legend of the Lone Ranger in 1981, a film plagued by so many production issues that it became a cautionary tale in Hollywood.

The lead actor’s entire voice had to be dubbed original Lone Ranger actor Clayton Moore was legally blocked from wearing the character’s mask in public, causing a media storm. The film flopped so badly that its star never acted again. Still, Jay Jr. continued in television, trying to walk the line his father had walked, being proud, being visible, and pushing for better roles for native actors.

Back in 1966, when Jay officially launched the Indian Actors Workshop, he said its main purpose was to tap into the dormant creativity of the Indians. That creativity didn’t stay dormant for long. In the years after his death, the workshop’s influence could be felt in the rise of native actors like Graham Green, who was Oscar nominated for Dances with Wolves and films like Smoke Signals in 1998.

The first feature written, directed, and produced by Native Americans. Jay’s name is carved into the concrete of Hollywood and the legacy of Native Cinema. He was postumously inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame in 1993 and the Canadian Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 1997 under the name Harry Tanto Smith. His portrait still hangs in Buffalo’s Shea’s Performing Arts Center.

His influence shows up in every indigenous storyteller who demands more than stereotypes and chooses to speak, act, and write on their own terms. And even though he once said he cringed inside every time he had to deliver Tanto’s broken English lines, he never let bitterness stop him. On the Tonight Show in 1969, he came out as Tanto, looked straight at the camera, and said, “My name is Tanto.

I hail from Toronto, and I speak Espiranto.” Even when the lines weren’t his own, Jay Silverhills knew how to reclaim the stage.

News

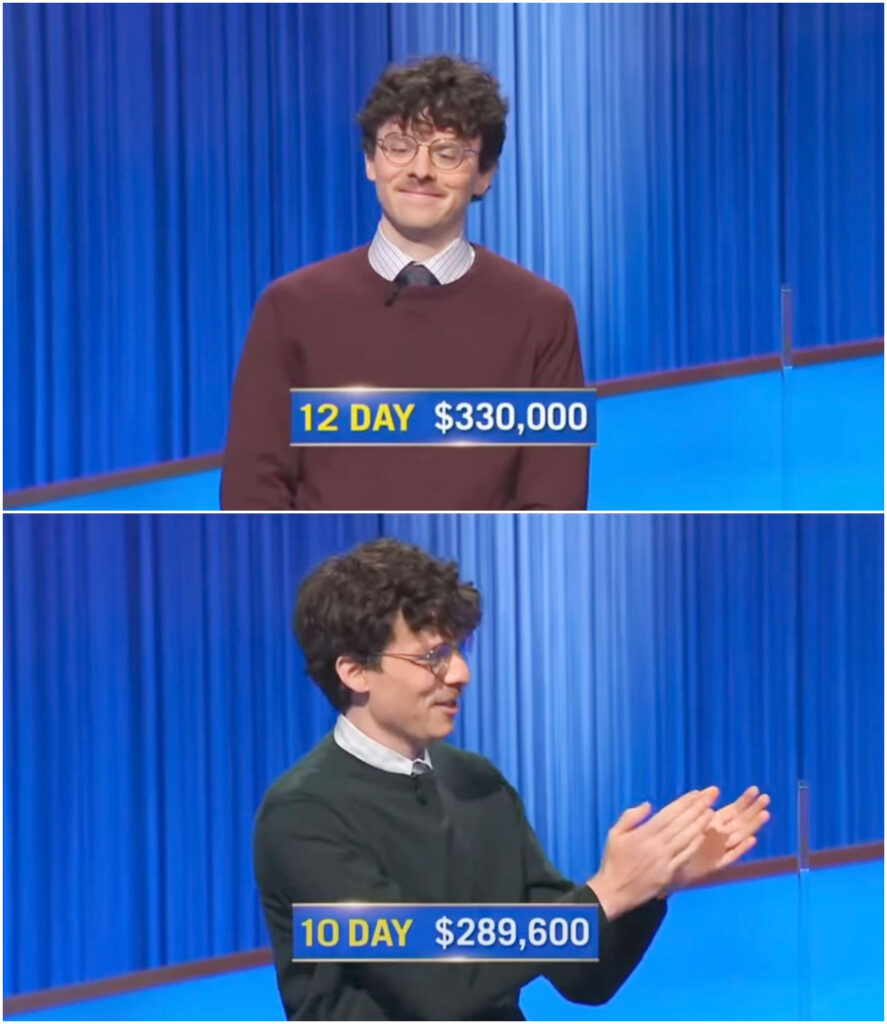

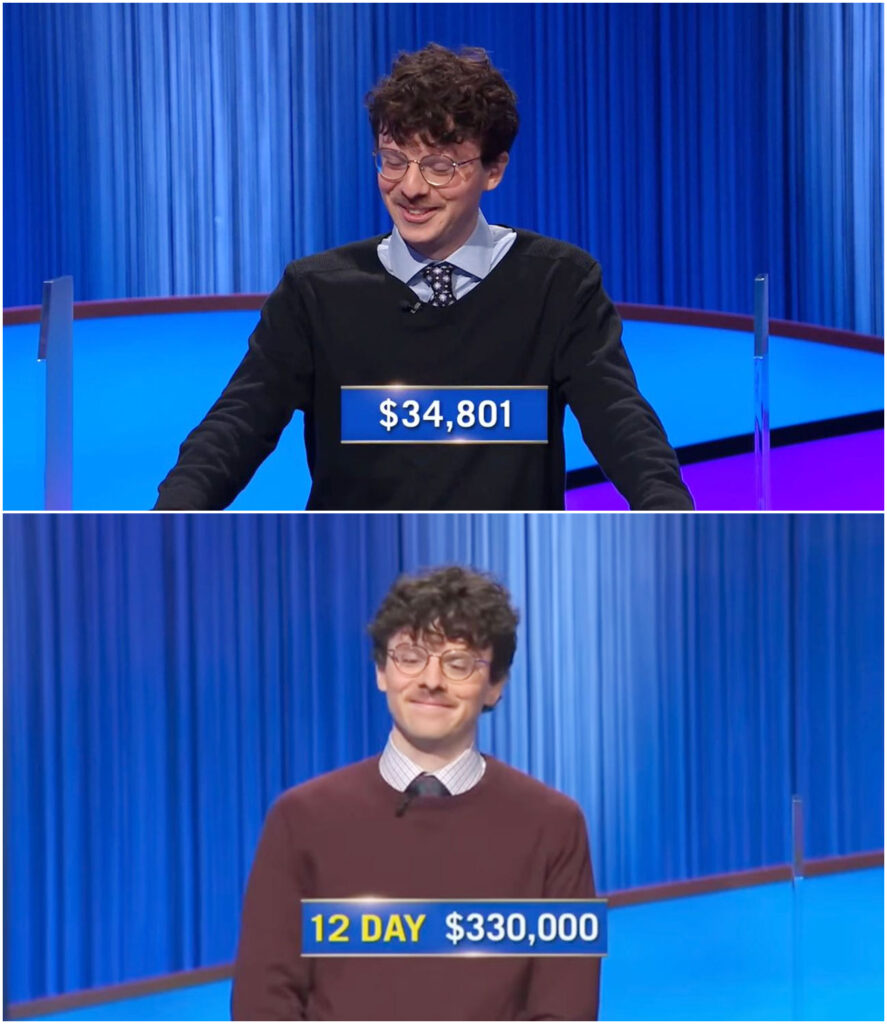

Double The Danger! Ron Lalonde Follows His Twin Brother Ray As A ‘Jeopardy!’ Champ: Did He Secretly Eclipse His Brother’s Eye-Watering Earnings Record?

Ron Lalonde follows twin brother as Jeopardy! champion with eye-watering earnings Twin brothers Ron and Ray Lalonde both became Jeopardy! Champs, while Harrison Whitaker’s 14-game streak ended View 3 Images Ron Lalonde has followed his twin brother Ron Lalonde followed in his twin brother’s footsteps this week by becoming a two-day Jeopardy! champion, echoing the […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Fans Complain They Don’t Like Celebrity Video Questions

‘Jeopardy!’ Fans Complain They Don’t Like Celebrity Video Questions Courtesy of ‘Jeopardy!’/YouTube Courtesy of ‘Jeopardy!’/YouTube What To Know Jeopardy! has recently featured celebrity video clues in some episodes, often as a way to promote upcoming releases or tie into themed categories. Many fans have expressed frustration on social media, arguing that these video clues disrupt the […]

3 times Ken Jennings has apologized on behalf of Jeopardy! and his actions

3 times Ken Jennings has apologized on behalf of Jeopardy! and his actions Ken Jennings is beloved for many reasons, and one of them is because the TV personality seems to know how to take accountability when it’s time whether it’s for him or Jeopardy! Jeopardy! host Ken Jennings isn’t too big to admit he’s […]

Jeopardy! fans slam ‘nonsense’ clues as one category is ‘the worst’

Jeopardy! fans slam ‘nonsense’ clues as one category is ‘the worst’ During the latest episode of Jeopardy!, viewers were outraged over one vocabulary category in the first round that had three clues which stumped all of the contestants View 3 Images Jeopardy! fans slam “nonsense” clues as one category is “the worst”(Image: Jeopardy!) Jeopardy! fans […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Champion Arrested on Felony ‘Peeping’ Charges

‘Jeopardy!’ Champion Arrested on Felony ‘Peeping’ Charges Jeopardy, Inc! Two-day Jeopardy! champion Philip Joseph “Joey” DeSena, who appeared on the long-running game show last November, was arrested on Monday, December 1, on two felony “peeping” charges. According to MyFox8.com, citing a warrant filed by the Currituck County Sheriff’s Office in North Carolina, DeSena is accused of installing cameras in a […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Contestant Reveals She Got Death Threats After Beating Ken Jennings Sony/Jeopardy! When you defeat a 74-game Jeopardy! champion, you’re expecting cheers and a pat on the back. However, Nancy Zerg received death threats for six months after winning her game against Ken Jennings. Zerg, now 69, has revealed in a new interview how her life was made hell after […]

End of content

No more pages to load