Lonely Lumberjack Paid $2 for Woman With Sack on Her Head at Auction—Marries Her When She Says Name.

Lonely lumberjack paid $2 for woman with sack on her head at auction marries her when she says name. Oregon territory. Spring of 1869. A dustworn outpost along the Oregon Trail. The scent of dry timber, horse sweat, and tobacco hangs thick in the air. Around the makeshift auction stage, nothing more than planks nailed to wagon crates. A crowd of men gathers.

Rough hands, dull eyes, hungry hearts, and hollow souls. The kind of place where even decency forgets to stop. A man with a faded blue vest and rusted deputy badge slams a wooden gavvel onto the post. All right, last one for the day, he bellows. She ain’t got no name. Ain’t shown her face.

Sack over the head since Missouri. Says she can work. Says she’ll obey. Starting bid, $2. Who’s brave or drunk enough to marry the mystery? Laughter breaks like a whip. Maybe she’s a witch under that thing, one man shouts. Or a corpse, says another. Might as well marry the damn sack. A few men spit into the dirt and turn away.

Others stay to watch, nudging each other, waiting for someone foolish enough to raise a hand. On the wooden platform, she stands still, barefoot, dusty, her hands bound in front with fraying twine. The sackcloth over her head is stained, too large, tied tight at the neck. Only her breathing betrays her fear. It comes quick, shallow, controlled, but barely. Her fingers twitch, clench, release.

She’s no good to anyone if she won’t even speak, the auctioneer grumbles. No one steps forward. Not for a long minute. Then the crowd parts like water. From the back, a tall figure walks forward. Broad shoulders beneath a canvas coat, a face shaded by the brim of a black hat, worn but clean.

His boots are heavy with mud, his shirt sweatlined, and his axand is wrapped in leather strips. A man who has lived more with trees than people. $2, he says. Silence falls like snow. The auctioneer squints. You sure, mister? I said what I said. His voice is low. Not angry, not eager, just certain. A few men snicker. Must be desperate.

The auctioneer clears his throat, nervous now. You do not want to see what you are buying. The man tilts his head toward the woman, still unmoving beneath the sack. I ain’t buying a face, he says quietly. I am marrying a person. Even the wind stops. No one laughs this time. Fame, the auctioneer mutters. Silus Boon. The profession. Lumberman, Northridge.

The auctioneer scribbles. Fine. Let it be known that Mr. Silas Boon, resident of Oregon territory, has entered lawful marital contract under the eyes of God and the witness of this court. He shoves the paper towards Silas, who signs without flinching. Then he turns to the woman. You’re now legally wed, miss. Say your name for the record.

The sack shifts slightly. No sound at first. Then very softly, so softly one has to lean forward to hear. The voice comes. Annabel crow. Silas freezes. The crowd leans in. The auctioneer raises an eyebrow but says nothing. Silus’s eyes widen. Just a flicker. Then they harden again. Fixed on the sack.

On the voice that now echoes in his mind three winters ago in the snow in the dark. A voice he never forgot. A name he never heard until now. And suddenly the forest silence, the bloody snow, the fire light in that frozen cave. It all rushes back. He steps off the platform slowly. Aches the woman’s arm.

Not roughly, not urgently, just firmly enough to say, “You are safe now.” No one stops them as they walk away. Not a word from the crowd, just the creek of boots over planks, and the whisper of a name that still trembles between them. Annabel Crow, the forest closed in around them as they walked, the trail narrowing to a thread of broken pine needles and packed earth.

The light dimmed beneath the canopy, sun straining through the thick boughs like it too was unsure whether to come closer. Annabelle said nothing. The sackcloth still covered her head, drawn tight around her neck, the edges fluttering in the evening breeze. Once the wind caught it enough to tug sideways, she reached up instantly, adjusting it with both hands, keeping her face hidden.

Silas Boon walked several paces ahead, leading the old mule that carried the few supplies they had been allowed from the outpost. He did not turn around, nor try to speak. He simply kept to the trail, every so often, glancing toward the trees, as if listening for more than wind. The silence between them was not awkward.

It was a silence carved from different kinds of survival. They reached the cabin before dusk. It was built from dark pine, not large, but tight, strong, clean, set against a rise of earth that blocked the worst of the north wind. There was a stone chimney, a stack of wood beside the door, and a rusted horseshoe nailed above the frame. Silas reached the door, pushed it open with a creek, then stepped aside.

“You pick where you stand,” he said quietly. “No one’s going to place you anymore.” Annabelle stepped in slowly. Her movements were cautious but not weak. She did not remove the sack. Her steps made almost no sound across the smooth wooden floor. She did not sit at the table.

She crouched against the far wall back to the room, hands resting on her knees, silent. Silas stepped in behind her, placed a bundle of firewood near the hearth, and began to work at the stove. No questions, no commands, only the occasional sound of iron shifting or water boiling. The scent came slowly, warm, thick, real, something with spice, quill of cinnamon, the salt of smoked meat. He worked in rhythm as if he had done this a thousand times before.

Annabelle did not move. When the food was ready, Silas placed a wooden bowl near her. She flinched slightly, but did not turn. He sat at the table with his own bowl, neither rushing nor staring. After several minutes, her voice came muffled but audible. Oh, what is this? Silas looked at his bowl, stirred once, and said, “I call it the meal for the last one standing.

” A pause, then a quiet sound, almost a breath of a laugh, but stifled, withdrawn. He added, “Used to make it for myself after long days in the woods. Then I started making two bowls, even when there was no one to eat the second.” She turned her head slightly, enough to glance sideways beneath the hem of the sack. On the chair beside him sat a second bowl, identical, steam rising from it. No one else in the room.

Silas gestured toward it. I used to set it for my wife after the war, after the trees took more than they gave. Just a way to say I came home alive again. He paused. Now I said it for you and for her. The silence held. The fire crackled. Annabelle reached for her bowl slowly.

Her hands trembled faintly, but she gripped the spoon and drew it under the sackcloth without removing it. She ate in silence, every bite small, careful, but she finished it. That night, while Silas washed the bowls in a tin basin near the stove, Annabelle remained by the wall, her knees drawn up, arms wrapped around them, watching, not speaking. But for the first time since he met her, she was not shaking.

That night, after the fire had died down to a steady glow, and the last embers of supper had been cleaned from the bowls, Silas sat alone before the hearth. He had not lit a lantern. He did not need it. The fire light was enough, casting long shadows that danced along the log walls like silent memories.

Outside, the wind moaned through the trees, long, low, and familiar. He leaned forward, elbows on knees, letting the warmth touch his face. But it was not warmth he felt, not entirely. It had been 3 years ago, a winter thicker than any before. The kind of cold that turned pine needles into glass and lungs into fire. He had gone too far north for timber.

Greedy for wood, stubborn with pride, he slipped on a slope, twisted his leg, and fell into a snowbank where no trail existed. By the time the snow covered his back, he had stopped fighting. But then, hands rough, calloused, a pull, dragging him. He remembered the pain, the jarring weight of his body moving against rock, then darkness.

He awoke to fire, a small cave hidden behind a curtain of ice. The fire cracked and hissed beside him, and the smell, something earthy, bitter, like boiled bark, filled his nostrils. Across from him sat a figure, a woman. Her face was hidden beneath a sackcloth tied carefully, just like the one in the cabin now.

She wore layers of scavenged wool and leather, boots stitched from scraps. Her hands moved with precision as she poured a ladle of steaming liquid into a tin cup. When she spoke, her voice was neither high nor low, only soft, measured, tired. You do not need to know who I am, she said. But I am not going to let you die. He had tried to speak, but no words came.

Drink this, she continued. It is pine bark and dry lychen. It will help the fever. He remembered the taste. Bitter, but he drank. She had wrapped his leg, set it against hot stones, kept the fire going through the night. He faded in and out, fighting the cold, the pain, and whatever dreams tried to steal him away.

When he woke again, morning, light blue and cruel, she was gone. Only the fire remained, low and guarded, and beside it, folded neatly, was a square of cloth, embroidered, purple flowers stitched in uneven thread no larger than a palm, a token, or perhaps a message. He kept it, still had it, folded inside his coat pocket.

And now in the cabin behind him, a woman sat with the same voice, the same quiet hands, the same sackcloth over her face, and a name. Annabel crow. He closed his eyes, leaning further into the fire. He did not need proof. He had felt it the moment she had spoken on that auction stage. Not the name, the sound.

The woman who had saved him had not wanted to be seen, not wanted to be known. And here she was again, still hidden, still nameless to the world, but not to him. He did not tell her that night. He let the memory live inside him, a silent agreement between past and present. He glanced back toward the small shape huddled near the far wall, sack still on her head, back still turned.

the same fear, the same need to disappear. But this time, Silas thought she was not alone. And that maybe was the start of something that could live beyond snow. The forest held its breath that morning. Mist clung low to the roots, curling around the base of the trees like secrets too shy to rise.

A soft wind passed through the needles above, high and slow, as if even it did not want to interrupt. Annabelle stepped outside the cabin alone. She moved quietly, arms folded across her middle and walked toward the tall pine that stood like a sentinel at the edge of the clearing. The sack still covered her head, but her steps no longer wavered.

Her spine was straighter now, not proud, but no longer bowed. At the base of the tree she sat, she turned her face slightly to where the early sun cut through the branches. She reached up with trembling hands and loosened the knot behind her neck. The sack slid up just far enough to let her breathe open-faced to the wind. Her mouth, her nose, a sliver of cheek. It was not defiance. It was a beginning.

H Silas saw her from the sideyard where he knelt beside a wooden basin, oiling the teeth of his saw. He did not rise, did not call out, but after a moment he spoke low, steady, as if saying it more to the trees than to her. I once got hurt bad, deep winter, got turned around near Black Ridge. I should have died out there.

His fingers moved over the blade, cleaning, but someone found me, pulled me into a cave, saved my life. Annabelle did not turn. She wore a sack over her head, would not say her name, barely let me see her hands. He paused, but I remember her voice. He turned his head just slightly, not to face her directly, but to let his words carry fuller.

Your voice sounds just like hers. There was a stillness and then a sound, the soft scratch of fabric sliding over skin. He did not move, not even when he felt her eyes on him. When he finally looked up, she was staring straight at him. The sack lay in her lap. Her face was not deformed. It was not monstrous.

It was human, but it bore a mark no one could miss. A long curved scar ran from her right temple to just above the line of her jaw. Not fresh, not bleeding, but deep, permanent, as though fingers, cruel and frantic, had tried to claw something from her that would not come free. She met his gaze, no longer hiding, but not proud either. Only bare. Her voice came in a whisper.

“The man who ran the boarding house where I worked, he told me I could keep a room if I gave extra.” She swallowed. I said, “No, he did not like that.” She looked down for a breath, then back to Silus. He came at me. I fought back, pushed him. He slipped. His head hit the stove. She stared past him now into memory. Aim died. I ran.

Silas’s jaw tightened, but he said nothing. They said I killed him on purpose, that I lured him, that it was all planned. Her voice wavered. There were no witnesses. No one believed me. She looked at her own hands. They called me a liar, a temptress, a killer. Silas stood, wiping his hands on a cloth. Annabelle went on, her tone low and even.

They sold me off to pay his debts, passed me along from one hand to another like cattle. They covered my face to make it easier, to make me nothing. She looked at the sack in her lap. I wore this so people would not look at me like I was poison, so they would not see the scar and decide what I was worth before I even spoke.

She looked up at him again, eyes glassy but fierce. I did not ask to be saved. I did not ask to be bought, but I am tired of hiding. Silas did not step forward. He did not touch her. He only nodded. Thank you, he said, for telling me. His voice was steady, warm, real. You did not have to, but you did. She blinked hard, but no tears fell. Only breath.

And in that breath, something shifted. For the first time since she arrived, she was not a shadow. She was a woman with a name, a story, and a face. And Silas had seen all three, and turned away from none. The sun crept slowly through the forest the next morning, its light, golden and tentative, spilling through the narrow window above the table.

Dust moat spun lazily in the beam like tiny spirits dancing between the wood grain walls, blessing the quiet. Inside the cabin, the air was still, not with fear, not anymore, but with the hush of understanding, like breath held in space after something fragile has been shared and carefully received. Annabelle had barely spoken since the day before, but she had not reached for the sack.

She no longer pulled it over her head before sleeping, no longer kept it folded at the foot of her bed like a shield waiting for battle. Her hair, untied and tangled from sleep, lay quietly against her shoulders as she rose from the cot. Her steps remained cautious, her posture guarded, but something in her presence had shifted. Something small, like the ground thawing beneath snow.

She blinked at the light pouring through the window and moved toward the table, expecting the usual, a tin of coffee, the wooden bowl she washed nightly, the leftover spoon. Instead, she stopped short. There was something new waiting for her. A small mirror. It stood upright, silverframed, aged at the edges, but polished to clarity. It leaned against a smooth wedge of pine, angled perfectly to catch the light of the rising sun, so that it would illuminate, not expose.

Beside it hung a scarf, sea green silk, faded slightly in parts, but soft and carefully folded, like it had been treasured once. maybe still was. There was no note, no gesture pointing toward it, just the mirror and the scarf placed there as if they had always belonged to that table, and as if she had always been meant to find them.

Annabelle stared at the objects for a long time. She did not move. Not at first. The fire in the stove had gone low, and only the crackling of old pine and the occasional creek of the beams overhead filled the room. Outside the forest began to stir, the rustle of a J-bird in the branches, the slow drip of dew from the eaves.

She approached the tables slowly, as if afraid the mirror might reflect something she could not bear. But when she reached it, she looked. What she saw was not new. She had felt her face a hundred times since the day her world cracked open. She knew the ridges of the scar, the path it carved down her cheek like a brand that never asked permission. Her hand lifted.

She touched the mark lightly the way one might touch a name etched into stone. Familiar, inevitable. But this time, this time under the sun through clean glass, she did not wse. The scar was still there. It always would be, but so was the woman behind it. Her gaze lingered, then shifted to the scarf. She lifted it with both hands. It slipped through her fingers like river water.

Cool, gentle, kind. There was care stitched into its every fiber. She brought it to her head, not to hide the scar, but to shape what others would see, to soften the outline, to take control of her own image, not out of shame, but of choice. The scarf settled into place like it belonged there.

In the mirror, a new figure emerged. Not the hunted girl from the auction. Not the ghost from the snowstorm, but a woman, full, upright, still carrying what she had lived through, but no longer buried by it. Behind her came a sound. Soft boots on plankwood. She did not turn. She did not need to. Silas stood in the doorway, one shoulder leaning against the frame. He had entered without a word, as was his way.

But the look on his face was not one of caution or surprise. It was quiet reverence. He tilted his chin toward the scarf. “That used to be my wife’s,” he said, voice steady. She wore it whenever she needed to feel like herself again. Annabelle’s fingers brushed the silk near her temple. “I thought maybe it would suit you too,” he added. She turned slightly toward him, not flinching, not defending.

He held her gaze, unwavering. Then with a voice as soft as moss and just as anchoring, he said, “Anyone who tries to make you ashamed of what you live through is blind.” A beat passed and the blind do not get to judge beauty. Her throat tightened. The tears came slow, but they came. Not sharp, not desperate, but warm, cleansing.

She looked at herself again. Then gently she reached out and laid her palm flat against the mirror. meeting her reflection halfway. And for the first time in a very long time, Annabel Crowe let herself be seen. The piece they had carved in the woods did not last unchallenged. It never did, not in these parts.

Trouble came on horseback, riding alone beneath a sky bruised with stormlight. The man was lean, long-legged, his duster torn from trail wind and mean miles. His eyes gray, sharp, merciless, cut through the saloon crowd like a blade through ripe hide. He called himself Cutter, and Cutter was no drifter.

He was a bounty hunter, the kind who could read tracks like scripture and smell secrets under boots. Rumor had drifted from the southern trail, a girl with a scar, hiding in the hills, face once covered, now showing. Someone whispered she had blood on her hands and a lumberman for a shield.

Cutter listened and then he rode. By the time he reached the logging post near North Ridge, he was asking too many questions. He posed as a lost traveler, claimed he was seeking work with the timbermen, said he heard tell of a man named Boon, who lived deep in the woods. Silas met him by chance near the supply shed.

One look and he knew, not by the words. Cutter was polite, measured, but the way he scanned the treeine, the stillness in his stance, it was the stillness of a snake just before the strike. Later that evening, Silas returned to the cabin. His face was colder than the wind. “He is hunting you,” he said simply.

“Anabel did not speak at first. She stood by the stove, stirring soup that had gone thin with memory. Her eyes were steady but far away. Then, without a word, she crossed the room, opened the wooden chest at the foot of the cot, and pulled out the old sackcloth, folded neatly, untouched since the morning she had shed it.

She held it in her hands for a long time. “I will wear it again,” she said quietly. “One more time.” Silas looked at her. “You do not have to.” Her eyes met his. This time, I choose it. Not for shame, for strategy. They laid the plan together that night. Annabelle would ride east through the old fire road. Wearing the sack, Cutter would follow. He would not resist a girl alone, scarred and covered, a ghost reborn.

Silas would take the mountain pass, ride cross, and meet with the sheriff in town. If the plan worked, Cutter would follow her straight into the trap. And it did. At dawn, with the sky barely blushing, Annabelle mounted Silas’s second horse and rode out, sacked tight over her head, heart hammering. She did not tremble this time.

She looked forward. By sundown, Cutter had taken the bait. He followed her deep into the eastern rocks, where Silas waited with the sheriff and two men from the ridge patrol. Cutter drew first, but not fast enough.

He was disarmed, bound, and thrown over the back of his own horse, charged with unlawful pursuit, attempted assault, and intent to kill. Annabelle watched it all from the hilltop, her form still hidden beneath the sack. Only onceQar was gone did she ride down. When she reached Silas, he stepped forward to help her down from the horse. She let him. Then, slowly, she reached up and untied the knot at the base of her neck. The sack slipped free.

She folded it once, twice, then held it in both hands, staring at the fabric. Silas watched her, unsure of what she would do. She looked up at him, her expression quiet, but no longer afraid. “It saved me one last time,” she said. “Not because it hid me, but because I used it.” He nodded.

“Then what will you do with it now?” She looked at the trees, at the fading trail, at the world she had once moved through like a shadow. She folded the sack one more time and tucked it beneath her arm. I will keep it, she said softly. Not as a cage, but as proof, Silas raised an eyebrow. Proof of what? She smiled.

That even what was once my prison can become my shield, if I choose it to be. And for the first time there was light in her voice. Not the light of laughter, but the light of a woman who had lived through the dark and now could name it. It was midafter afternoon when the knock came. A slow, uncertain tapping. Not the kind of knock that demanded, “Ha!” But the kind that asked permission.

Silas opened the cabin door to find a woman standing on the porch. Her dress was worn, travel stained, and her boots carried the red dust of long roads. Her skin was dark, her posture straight, her eyes cautious but kind. She held her hat in both hands. “Name’s Mavis.” “Mavis Green,” she said. “I used to work at the Ridley House. Kitchen help. Cook mostly.

” Behind Silas, Annabelle stepped into the doorway. “She froze when she saw the woman.” Mavis took a step back, then stopped herself. “I heard you were up this way,” she said quietly. and I figured it was time I stopped being a coward. The wind rustled through the pines as silence stretched between them.

I saw what happened that night, Mavis said. Saw him drag you into that back room. Heard you scream. Heard the crash. But I did not speak up. I needed the job. I needed to eat. Annabelle’s fingers tightened against the door frame. I am not proud of that, Mavis continued. But I can make it right now if you will let me.

Later, over tea at the table, Mavis recounted everything, details only someone who had truly been there could know. She described the bruises, the blood, the silence that followed. “I should have said it back then,” she whispered. “But I will say it now. You were telling the truth.” With Silas’s help, they wrote it all down.

Mavis signed the affidavit in strong, careful penmanship. The letter was sealed and sent to the nearest judicial office by horseback courier. Weeks passed. The forest grew greener. The sky turned warmer. Then one morning, the sheriff rode up with a single envelope in hand. Silas opened it on the porch, read it twice before walking it inside. Annabelle took it in her hands.

The words were few. Charges against Annabelle Crow dropped. Case closed. warrant rescended. She read them again and again. Then she walked outside, past the firewood pile, past the horses, and down to the treeine. She found the old pine, the one she had once buried her sackcloth beneath.

She sat at its base, running her fingers through the moss, breathing. She did not cry. She did not laugh. She just closed her eyes. And in a voice barely more than breath, she said, “For the first time in my life, I do not have to run. Justice had come, not with trumpets, not with applause, only with truth, and the quiet strength of someone who had finally decided to stand beside it.” Spring came gently to the ridge.

The trees, once bare and brittle, now wore soft buds, like promises waiting to bloom. Mist still rolled in at dawn, but it was thinner, lighter, as though even the fog had grown tired of hiding. Birds sang again. The river moved with purpose. The forest felt forgiving. Silas had been busy. With spare wood and a quiet kind of care, he built a modest canopy just outside the cabin, near the edge, where wild flowers began to claim the grass. It was nothing grand.

four upright beams, a simple arch draped in linen, but it stood strong like him. They invited only a few. Mavis came, smiling wide in a dress that did not match, but still suited her spirit. The old blacksmith from town brought a bottle of apple brandy. The shopkeeper’s wife carried a basket of bread and a bouquet of mountain lavender.

They were not many, but they were enough. Inside the cabin, Annabelle stood before the small mirror Silas had left for her months ago. Her dress was plain muslin, handstitched, the color of cream, but it fit her perfectly because she had made it herself with steady fingers and quiet nights. On her head she wore a veil.

It was made from the sackcloth, the same one that had once hidden her shame, her fear, her name. But now it was something else. Silas had washed it, sundried it, and cut it with care. The edges were sewn with white thread, the kind used for mending old linen.

And on the corners, embroidered in faint purple, were tiny wild flowers, almost identical to the ones stitched into the handkerchief she had once left behind in the snow. When she stepped out of the cabin, the forest fell still. Silas stood beneath the wooden arch, hands folded, heart full. He had trimmed his beard, polished his boots, and ironed the only shirt he owned without sap stains.

But none of that mattered when he saw her. She moved slowly like the earth had finally given her permission to be seen. And she was beautiful, not because the veil covered the scar, but because she had chosen to wear it again on her terms. As she reached him, Silas took her hands. His voice was low, but every word was steady.

No matter what covered your face, he said, you were always the woman I chose from the start. He paused, looking into her eyes. And now you are the woman I vow to stand beside to the end. Annabelle smiled, not with the caution of someone who had been hurt, but with the peace of someone who had finally healed.

He whispered, “And I vow the same.” There was no priest, no vows read from books, just them and the trees and the people who mattered most. And when they kissed, soft and sure, the wind picked up just enough to rustle the linen overhead. A few drops of rain fell, light as breath. Mavis leaned close to the blacksmith and said, “Not quite allowed. Never thought I’d see a burlap sack turned into a wedding veil.

” Then after a beat, she added, “Never thought it could be so damn beautiful.” The blacksmith chuckled. “Ain’t the sack,” he said. “It’s what she turned it into.” Later that evening, as the fire crackled and laughter mingled with bird song, Annabelle sat beside Silas on the porch. The veil lay folded in her lap.

She ran her fingers across the embroidered edge. “Funny,” she said. “This thing used to mean everything I feared.” He looked over. “And now?” She smiled. “Now it means everything I chose.” Silus nodded. He reached over, lacing his fingers through hers. They sat that way until the stars came out.

And the forest, once their prison, now held them like home. And so beneath the towering pines, and a veil once born of shame, Annabel Crowe and Silas Boon found what so many had lost on the frontier. peace, not in forgetting the past, but in reclaiming it. Their love did not erase the pain, the scars, or the silence.

But it turned what once bound them into something that could bless them. Because sometimes in the Wild West, survival was not just about holding on. It was about choosing what to hold on to. Thank you for riding with us through this journey of redemption, courage, and quiet devotion. If stories like this move your heart and stir your soul, do not forget to subscribe to Wild West Love Stories, where love rides farther than fear, and even the roughest trails can lead home. Tap the bell so you never miss the next tale.

Until then, ride steady, love deep, and remember, where bullets missed, hearts did not.

News

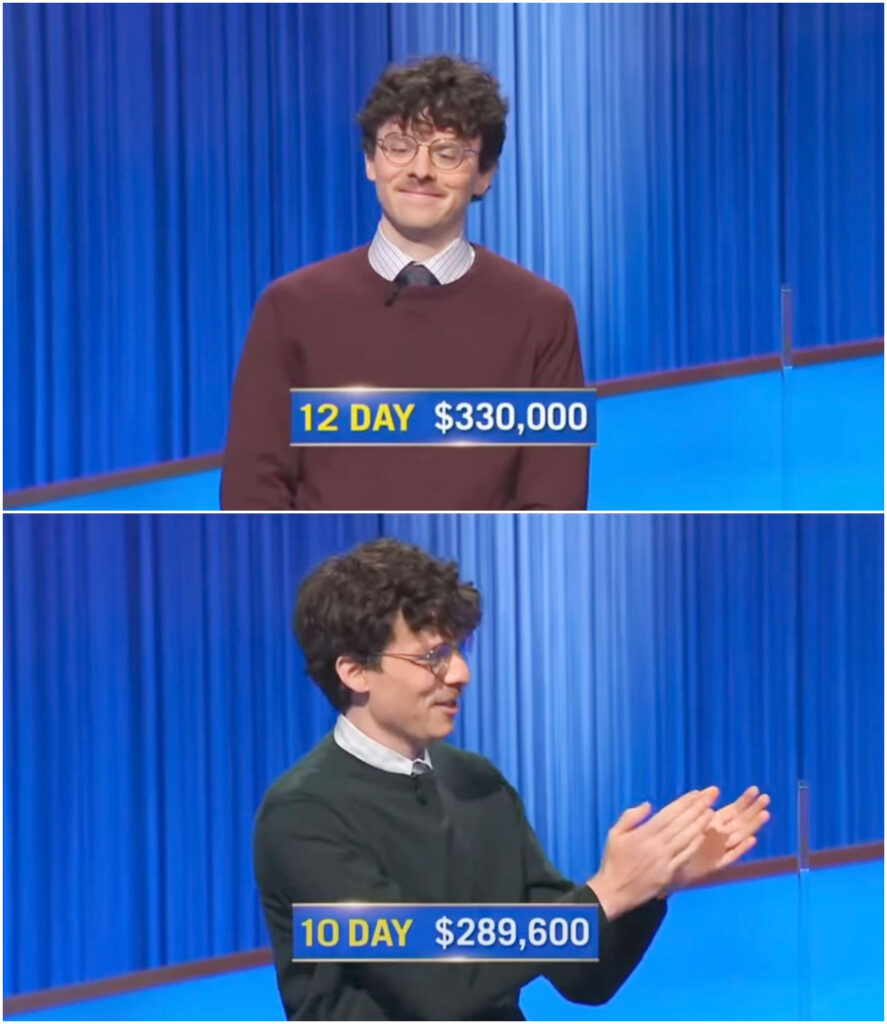

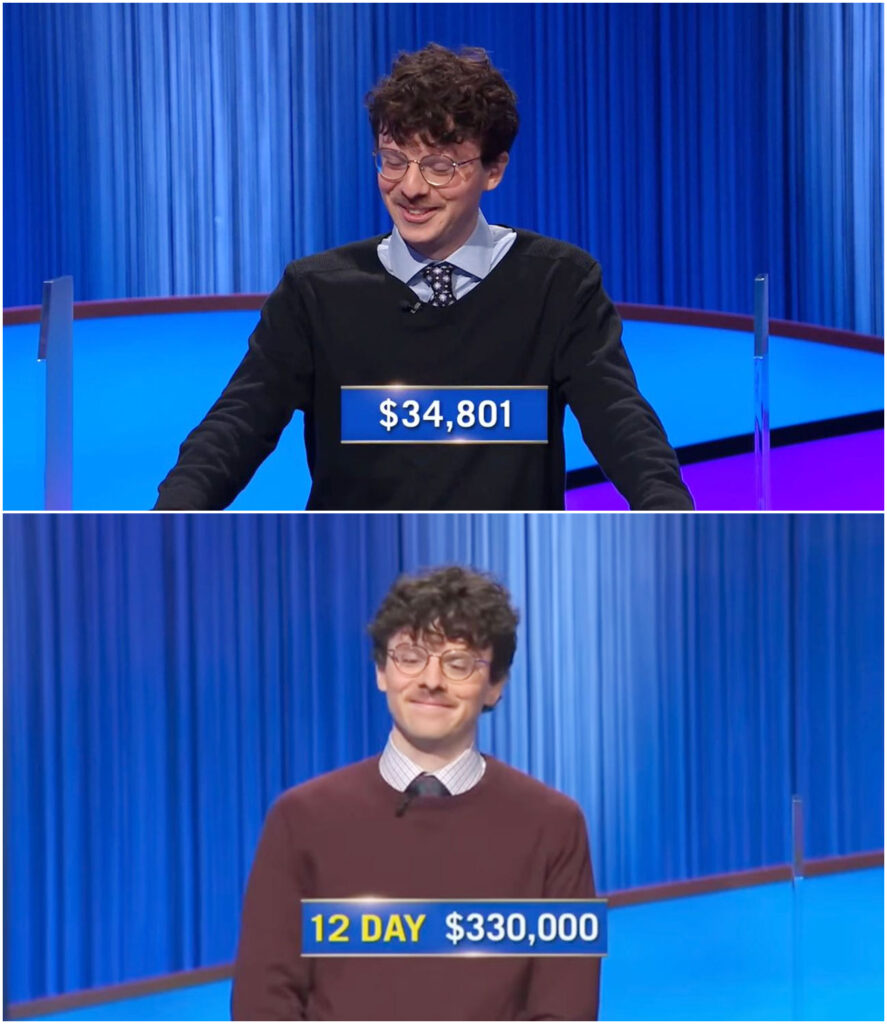

Double The Danger! Ron Lalonde Follows His Twin Brother Ray As A ‘Jeopardy!’ Champ: Did He Secretly Eclipse His Brother’s Eye-Watering Earnings Record?

Ron Lalonde follows twin brother as Jeopardy! champion with eye-watering earnings Twin brothers Ron and Ray Lalonde both became Jeopardy! Champs, while Harrison Whitaker’s 14-game streak ended View 3 Images Ron Lalonde has followed his twin brother Ron Lalonde followed in his twin brother’s footsteps this week by becoming a two-day Jeopardy! champion, echoing the […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Fans Complain They Don’t Like Celebrity Video Questions

‘Jeopardy!’ Fans Complain They Don’t Like Celebrity Video Questions Courtesy of ‘Jeopardy!’/YouTube Courtesy of ‘Jeopardy!’/YouTube What To Know Jeopardy! has recently featured celebrity video clues in some episodes, often as a way to promote upcoming releases or tie into themed categories. Many fans have expressed frustration on social media, arguing that these video clues disrupt the […]

3 times Ken Jennings has apologized on behalf of Jeopardy! and his actions

3 times Ken Jennings has apologized on behalf of Jeopardy! and his actions Ken Jennings is beloved for many reasons, and one of them is because the TV personality seems to know how to take accountability when it’s time whether it’s for him or Jeopardy! Jeopardy! host Ken Jennings isn’t too big to admit he’s […]

Jeopardy! fans slam ‘nonsense’ clues as one category is ‘the worst’

Jeopardy! fans slam ‘nonsense’ clues as one category is ‘the worst’ During the latest episode of Jeopardy!, viewers were outraged over one vocabulary category in the first round that had three clues which stumped all of the contestants View 3 Images Jeopardy! fans slam “nonsense” clues as one category is “the worst”(Image: Jeopardy!) Jeopardy! fans […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Champion Arrested on Felony ‘Peeping’ Charges

‘Jeopardy!’ Champion Arrested on Felony ‘Peeping’ Charges Jeopardy, Inc! Two-day Jeopardy! champion Philip Joseph “Joey” DeSena, who appeared on the long-running game show last November, was arrested on Monday, December 1, on two felony “peeping” charges. According to MyFox8.com, citing a warrant filed by the Currituck County Sheriff’s Office in North Carolina, DeSena is accused of installing cameras in a […]

‘Jeopardy!’ Contestant Reveals She Got Death Threats After Beating Ken Jennings Sony/Jeopardy! When you defeat a 74-game Jeopardy! champion, you’re expecting cheers and a pat on the back. However, Nancy Zerg received death threats for six months after winning her game against Ken Jennings. Zerg, now 69, has revealed in a new interview how her life was made hell after […]

End of content

No more pages to load